Scroll to:

Clinical cases of an accessory spleen in the pelvic and pelvic splenosis

https://doi.org/10.21886/2219-8075-2023-14-4-83-88

Abstract

The article describes cases of diagnosis of an additional spleen in the pelvis and splenosis of the pelvis in women, detected by ultrasound, confirmed by MRI. The relevance of the publication of the presented observations is determined by the rarity of such localization of the spleen and splenosis in the pelvis and the low awareness of obstetricians and gynecologists, most often conducting ultrasound examination of pelvic organs, about this pathology. Cases of an accessory spleen and splenosis in the abdomen are known and written in the literature, while similar findings in the pelvis are, firstly, a rare find, and secondly, ultrasound examination in gynecology is carried out by obstetricians-gynecologists, who rarely meet with surgical pathology, thirdly, the echographic picture requires differential diagnosis with endometrioma, hemangioma, primary and metastatic cancer, and splenosis and accessory spleen should also be differentiated from each other. The article presents two of our own clinical cases of splenosis and accessory spleen with US and MRI data, discusses the reasons for difficulties in diagnosis and key criteria for differential diagnosis, and also includes a review of the literature on this topic. Based on all of the above, it was concluded that should not forget about such a rare but possible diagnosis as pelvic splenosis, and also remember about a possible congenital condition – accessory spleen.

Keywords

For citations:

Strupeneva U.A., Efimova-Korzeneva O.A., Kluchnikova E.I. Clinical cases of an accessory spleen in the pelvic and pelvic splenosis. Medical Herald of the South of Russia. 2023;14(4):83-88. (In Russ.) https://doi.org/10.21886/2219-8075-2023-14-4-83-88

Introduction

Approximately 10% of the general population have an accessory spleen as separated nodules of healthy splenic tissue. Accessory spleens may vary in size, typically ranging from one to several centimeters [1]. Splenosis occurs as a result of traumatic splenic rupture or splenectomy. The proliferation of spleen cells initiates upon spleen rupture or splenectomy, when the spleen pulp enters the abdominal cavity and is auto-transplanted to an ectopic site [2]. In 1896, Albrecht was the first to describe the ectopic overgrowth of spleen tissue. The term "splenosis" was later introduced by Buchbinder and Likoffin in 1939 [3]. Thus, the accessory spleen originates from a congenital etiology, whereas splenosis is an acquired condition. Splenosis refers to the regeneration of spleen tissue that has been disseminated into the abdominal cavity due to injury or bleeding. Hematogenic and lymphogenic pathways have been described in addition to the contact mechanism of splenosis. Intrathoracic splenosis and brain splenosis can develop without damage to the diaphragm [4]. Splenosis can typically be found in various locations throughout the body, including the serous layer of the colon, the great omentum, and the peritoneum. Less commonly, it is localized in the liver, stomach, pancreas, chest, diaphragm, and anterior abdominal wall, while the kidneys, ovaries, and subcutaneous fat are considered uncommon locations. One case of splenosis detected in the brain has been reported [2]. Splenosis may present as single or multiple foci.

Splenunculus, or a congenital accessory splenic nodule, is considered a normal anatomical variant that may result from impaired embryonic development at 5–6 weeks of gestation. It is usually localized in the splenic hilum or near the tail of the pancreas, but can also be found in the mesentery of the small intestine, the great omentum, and the gastric wall [5]. There have been reports of uncommon cases of the accessory spleen localized in the pelvis and scrotum. The spleen is originally developed in the vicinity of the urogenital ridge (the future gonads). During development, the gonads may fuse with the nearby splenic tissue and descend through the abdominal cavity, displacing the splenic tissue [6].

If the accessory spleen is located near the primary organ, diagnosis is typically not problematic. However, difficulties in diagnosing an accessory spleen may arise if it is located in an uncommon area, such as the pelvis, due to the rarity of such localization and the lack of knowledge among specialists. Ultrasonic examinations of the pelvis are frequently performed by obstetricians and gynecologists who may not be prepared to identify non-gynecological pathologies in this area. Splenosis and accessory spleens are typically benign conditions with no clinical manifestations. However, in rare cases, an additional lobule may cause abdominal or pelvic pain when its vascular pedicle becomes twisted. As splenosis is typically benign and asymptomatic, and regenerative nodules may not appear until several years or even decades after the initial injury, it can be challenging to identify. Moreover, in cases of abdominal splenosis, clinical symptoms may present as an acute abdomen, while intrathoracic splenosis may cause hemoptysis. Diagnosis of splenosis can be challenging, especially when it imitates primary diseases of other organs, such as hepatic, ovarian, or intestinal neoplasms [2]. There are very few reports of pelvic splenosis in journals published in the Russian and English languages. Additionally, there is limited data on the spread of splenosis to the female reproductive system. This can manifest as isolated ovarian splenosis, which can mask an ovarian tumor, or extensive pelvic splenosis [7]. This paper presents two case reports: a pelvic accessory lobule of the spleen (case 1) and pelvic splenosis (case 2), which were challenging to diagnose due to their unusual location.

Case 1

A 40-year-old female patient presented to her gynecologist for a scheduled insertion of an intrauterine device.

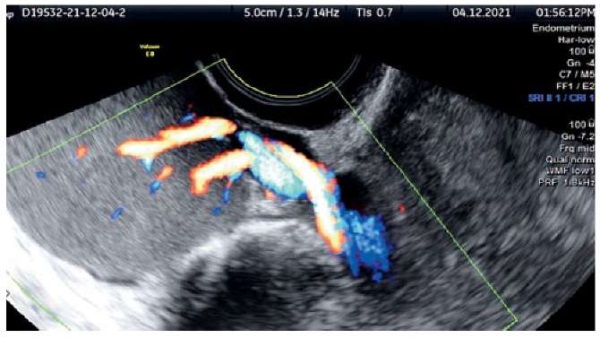

A pelvic ultrasound showed a round, solid mass 39×40×41 mm in size localized between the posterior surface of the uterus and the right ovary. The solid mass was highly vascularized as shown by a color Doppler imaging (CDI), with a clearly visualized vascular pedicle composed of a vein and artery (Figures 1–4).

Figure 1. Echogram of the accessory spleen

with a vascular pedicle in color Doppler mapping mode

Figure 2. Echogram of the accessory spleen (marked with markers)

and the right ovary (B-mode).

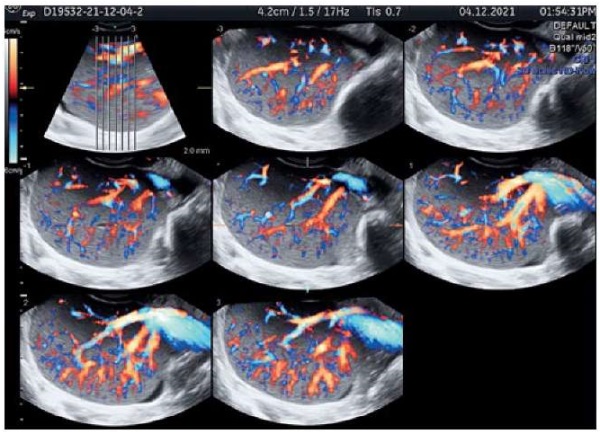

Figure 3. Echogram of the accessory spleen (TUI mode)

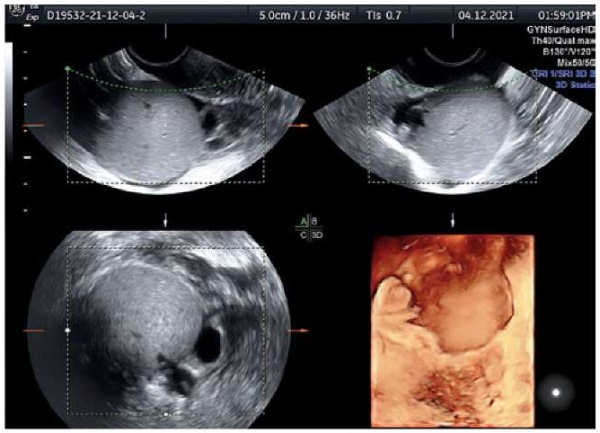

Figure 4. Echogram of the accessory spleen (volumetric reconstruction mode).

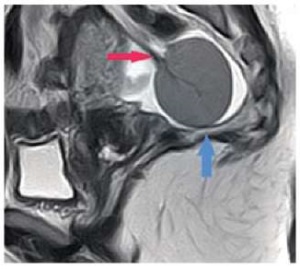

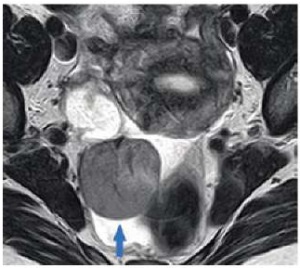

These findings suggested a misplaced spleen. No other ultrasonic findings related to abdominal or pelvic pathology were detected. The kidneys, pancreas, liver, and spleen were observed to be of normal size, shape, structure, and location. The ultrasound examination revealed that the uterus and both ovaries were structurally normal. The Voluson E8 ultrasound machine was utilized with both curved array and transvaginal probes. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was performed to confirm the hypothesis of an accessory spleen located in the pelvis. The MRI demonstrated an intraperitoneal mass located posteriorly to the uterus (Figures 5 and 6) with a vascular pedicle (Figure 5). The mass showed an intense homogeneous enhancement in the arterial phase (Figure 7), and no contrast washout was observed (Figure 8). The MRI findings were a hyperplastic accessory lobule of the spleen in the pelvic region.

Figure 5. MRI examination:

accessory lobule of the spleen (blue arrow) in the sagittal plane.

Vascular pedicle of the accessory spleen (red arrow).

Figure 6. MRI examination:

accessory lobule of the spleen in the transverse plane (blue arrow).

Figure 7. MRI study: typical for the spleen,

“mosaic” contrast in the arterial phase of scanning (green arrow)

Figure 8. MRI study:

intense homogeneous contrast in the delayed phase,

without washout in the additional lobe of the spleen of the pelvic localization.

Case 2

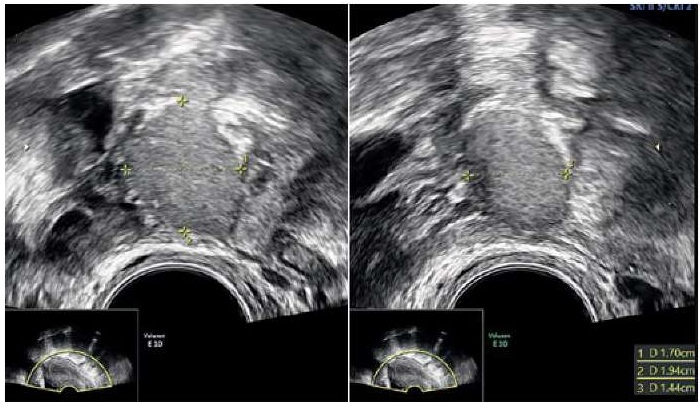

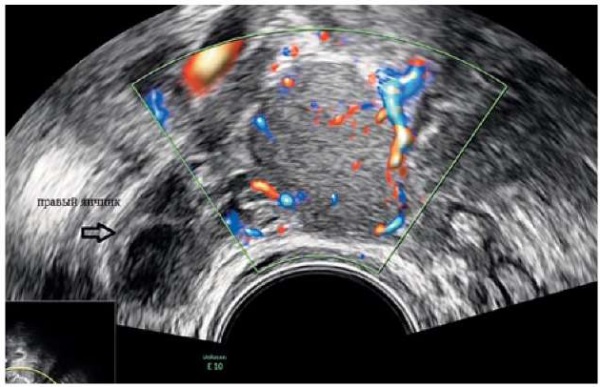

A 20-year-old female patient presented to her gynecologist for a routine checkup and contraceptive counseling. The patient was asymptomatic at the examination. She was examined using the Voluson E10 ultrasound machine with a RIC 6-12-D transvaginal probe. A smooth solid mass 17×19×14 mm in size was observed close to the right ovary (between the ovary and the uterus). No wall penetrations were found. The solid mass echogenicity was described as isoechogenic. The CDI showed moderate blood flow inside the mass (Figures 9 and 10).

Figure 9. Echogram of a solid pelvic mass

with measurements (three mutually perpendicular dimensions): splenosis

Figure 10. Echogram of a solid pelvic mass: splenosis (CDC mode).

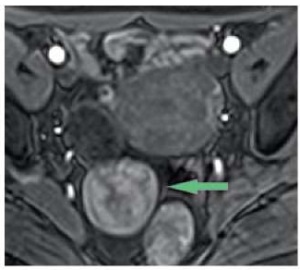

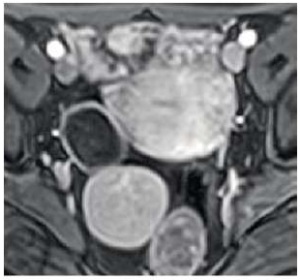

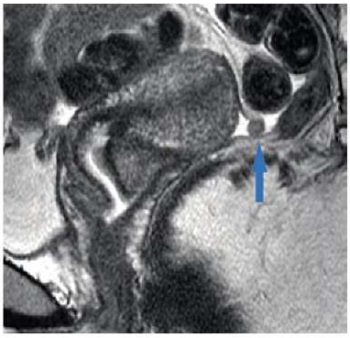

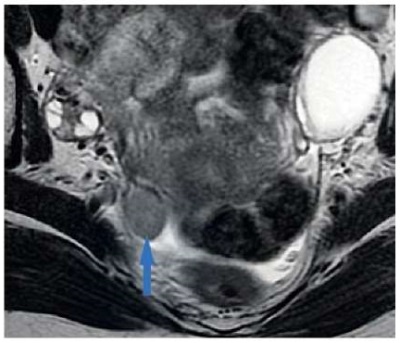

No other ultrasound findings indicative of pelvic pathology were detected. The patient's kidneys, pancreas, and liver were observed to be of normal size, shape, structure, and location. However, the spleen was not visualized in its normal position. The patient had a history of splenectomy at the age of 6 for mononucleosis. The preliminary diagnosis of splenosis was made. The doctor ordered an MRI scan to confirm the diagnosis. The MRI showed two masses visualized behind the uterus (Figures 11–13). These masses did not have a vascular pedicle and had MR characteristics that were similar to normal spleen tissue (Figure 14). Based on the patient's medical history, ultrasonic and MRI findings, a diagnosis of pelvic splenosis (two foci) was made.

Figure 11. MRI study: focus of splenosis (blue arrow) posteriorly

from the uterus in the sagittal plane.

Figure 12. MRI study: second focus of splenosis (green arrow)

in the sagittal plane of sanitation.

Figure 13. MRI study: focus of splenosis in the axial plane (blue arrow).

Figure 14. MRI study: heterogeneous intense contrasting of foci of splenosis

in the arterial phase.

Discussion

The reported cases provide clinical evidence of an uncommon pelvic location of the accessory spleen and splenosis. A review of the relevant literature has revealed that there is no standardized classification for ectopic spleens. Additionally, there are few publications in both Russian and foreign literature regarding ovarian splenosis. Incidental findings of splenosis may be misdiagnosed as a primary tumor or metastases of other tumors [8–12]. Therefore, splenosis should be considered in the differential diagnosis for neoplasms in patients with a history of spleen surgery or injury. It is important to differentiate pelvic splenosis from endometrioma, hemangioma, primary tumors, and metastatic processes. It should also be differentiated from the ectopic accessory spleen. Unlike splenosis, this is a congenital condition, which is supplied through a vascular pedicle from branches of the splenic artery. Splenosis is characterized by a through-flow of blood, i.e. the vessels penetrate directly through the capsule over the entire surface of the solid mass. Because most patients are asymptomatic, these conditions are most often an incidental finding on the ultrasound or MRI. The echography visualizes a hypoechoic or isoechoic mass with sharp and smooth contours. Its echographic pattern is similar to that of spleen tissue, with arteries and veins identified by the CDI. In case #2, a single isolated mass was found because of the small size of the second focus. It was located close to the right ovary. So it might be categorized as an O-RADS 4 solid mass (a solid mass with a smooth outer contour without acoustic shadows, with the CDI visualizing a moderate blood flow in the absence of ascites), which requires an oncology consultation. The MRI identified solid masses having MR signs similar to those of normal spleen stroma with high-intensity early heterogeneous enhancement indicative of splenosis. So if there are no other signs or symptoms, the diagnosis is limited to stating this feature. It should also be noted that the echographic pattern of splenosis is similar to that of an endometrioid cyst. They can be differentiated on the CDI. Endometriomas are avascular, while splenosis recruits a through-flow of blood.

Conclusion

If a physician detects a solid mass in the pelvic region of a patient with a history of spleen removal or injury, it is important to consider the possibility of pelvic splenosis or a congenital condition such as an accessory ectopic spleen in the pelvis.

References

1. Ryan S, McNicholas M, Eustace S. Anatomy for Diagnostic Imaging. Moscow: MEDpress-inform; 2009. (In Russ.)

2. Gubergrits N.B., Zubov A.D., Borodiy K.N., Mozhyna T.L. Splenosis: fetters of the unknown or step through existing precautions (part II). Medical Visualization. 2021;25(1):80-93. (In Russ.) https://doi.org/10.24835/1607-0763-925

3. Buchbinder JH, Lipkoff CJ. Splenosis: multiple peritoneal splenic implants following abdominal injury. Surgery. 1939;6(6):927-934.

4. Zinov'ev A.V., Kriuchkova O.V., Markina N.Iu. The formation of a tissue mass in the left hypochondrium region. Russia journal of evidence-based gastroenterology. 2013;2(4):58-62. (In Russ). eLIBRARY ID: 21537957 EDN: SDIEVP

5. Bajwa SA, Kasi A. Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis: Accessory Spleen. [Updated 2023 Jul 17]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023. (accessed on June 07, 2023) https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK519040/

6. Timerbulatov V.M., Fayazov R.R., Hasanov A.G., Timerbulatov M.V., Kayumov F.A., et al. Splenosis in surgical practice. Annals of HPB surgery. 2007;12(1):90-95. (In Russ.) eLIBRARY ID: 11744328 EDN: JXAARF

7. Karpathiou G, Chauleur C, Mehdi A, Peoc'h M. Splenic tissue in the ovary: Splenosis, accessory spleen or spleno-gonadal fusion? Pathol Res Pract. 2019;215(9):152546. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.prp.2019.152546

8. Bogomolov O, Shkolnik M, Stanzhevskiy A, Ivanova A,Dolbov A. Features of diagnosis and treatment of a patient with cancer of the right kidney in combination with disseminated abdominal and retroperitoneal splenosis. Voprosy onkologii = Problems in oncology. 2018;64(4):533-538. https://doi.org/10.37469/0507-3758-2018-64-4-533-538

9. Strokin K.N., Chemezov S.V. Ectopic spleen tissue after undergoing splenectomy (case study). Orenburgskii meditsinskii vestnik. 2017;5(2):50-51. (In Russ.) eLIBRARY ID: 29365069 EDN: YSPMNH

10. Short NJ, Hayes TG, Bhargava P. Intra-abdominal splenosis mimicking metastatic cancer. Am J Med Sci. 2011;341(3):246-9. https://doi.org/10.1097/maj.0b013e318202893f

11. Zubov A.D., Litvin A.A., Gubergrits N.B., Chernyaeva YU.V., Ushakova A.YU. The progressing multiple splenosis: paper review and own observation. Vestnik IKBFU. Natural and medical sciences. 2020;(4):104-117. (In Russ.) eLIBRARY ID: 44392372 EDN: SWJLLL

12. Smoot T, Revels J, Soliman M, Liu P, Menias CO, et al. Abdominal and pelvic splenosis: atypical findings, pitfalls, and mimics. Abdom Radiol (NY). 2022;47(3):923-947. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00261-021-03402-3

13.

About the Authors

U. A. StrupenevaRussian Federation

Ulyana A. Strupeneva – associate professor of the Department of Radiation Diagnostics and Biomedical Imaging

St. Petersburg

Competing Interests:

Authors declares no conflict of interest

O. A. Efimova-Korzeneva

Russian Federation

Olesia A. Efimova-Korzeneva – ultrasound diagnostician, obstetrician-gynecologist

St. Petersburg

Competing Interests:

Authors declares no conflict of interest

E. I. Kluchnikova

Russian Federation

Ekaterina I. Kluchnikova – radiologist of the Department of Magnetic Resonance Imaging

St. Petersburg

Competing Interests:

Authors declares no conflict of interest

Review

For citations:

Strupeneva U.A., Efimova-Korzeneva O.A., Kluchnikova E.I. Clinical cases of an accessory spleen in the pelvic and pelvic splenosis. Medical Herald of the South of Russia. 2023;14(4):83-88. (In Russ.) https://doi.org/10.21886/2219-8075-2023-14-4-83-88