Scroll to:

Screening diagnosis of mental distress and alcohol consumption in acutely ill somatic patients

https://doi.org/10.21886/2219-8075-2025-16-2-43-54

Abstract

Objective: to study, using the SCL-5 questionnaire, the prevalence of mental distress in relation to alcohol consumption, socio-demographic and some clinical characteristics among somatic patients hospitalized in a clinical hospital. Materials and methods: the material was collected in 2016–2017 in V. P. Demikhov City Clinical Hospital of Moscow. 3009 patients were included in the study. Basic socio-demographic data were collected. Alcohol consumption was assessed using AUDIT-4, and the state of mental distress was assessed using SCL-5. Results: the number of women with more than two SCL- 5 points exceeded the number of men. Divorcees and widows were in mental distress more often. The distribution of the number of patients with distress according to the AUDIT-4 test zones had a “J”-shape. The groups “Therapeutic profile” and “Cardiologic profile” were the most prone for distress. Conclusion: early recognition and correction of mental distress in individuals with harmful alcohol use in primary care may improve patient compliance and treatment outcomes. The SCL-5 questionnaire has been shown to be a concise and convenient tool for diagnosing mental distress.

Keywords

For citations:

Nadezhdin A.V., Tetenova E.J. Screening diagnosis of mental distress and alcohol consumption in acutely ill somatic patients. Medical Herald of the South of Russia. 2025;16(2):43-54. (In Russ.) https://doi.org/10.21886/2219-8075-2025-16-2-43-54

Introduction

Harmful alcohol use and somatic diseases are significant risk factors for mental disorders, including psychological distress, which is manifested primarily through anxiety disorders and, to a lesser extent, depression [1][2]. Psychological distress refers to a set of deviations from mental well-being that do not meet standard diagnostic criteria and are characterized by symptoms such as depression, insomnia, fatigue, irritability, forgetfulness, difficulties with concentration, and somatic complaints, including sleep disturbances and various types of pain. Numerous authors define psychological distress as encompassing symptoms of anxiety and depression [3][4] or as a state of emotional suffering marked by depressive symptoms (e.g., loss of interest, sadness, feelings of hopelessness) and anxiety symptoms (e.g., worry, tension) [5]. The nosological status of psychological distress in psychiatry remains ambiguous and is discussed extensively in the scientific literature [6][7]. For a more detailed examination of this topic, we refer to the comprehensive work by Drapeau, Marchand, and Beaulieu-Prevost (2011) [6].

Among inpatients with chronic somatic diseases, the prevalence of mood disorders, anxiety disorders, somatoform disorders, and substance use disorders is reported to reach 43.7% [8]. Studies indicate that the prevalence of psychological distress among hospitalized patients ranges from 53.1% to 58.6% [9][10]. Based on a systematic review of psychological distress in patients presenting to emergency departments for somatic conditions, Faessler et al. (2015) reported prevalence estimates between 4% and 47%, noting associations with demographic factors, disease characteristics, and frequent underdiagnosis of psychological distress during routine medical care [11].

Research on the relationship between psychological distress and alcohol use is limited. This association appears to be complex and nonlinear, necessitating careful interpretation of findings. For example, in men, both irregular/occasional drinking and hazardous/harmful drinking are linked to lower positive affect and higher psychological distress, whereas in women, elevated distress levels were associated only with hazardous or harmful alcohol use [12][13]. Among Afghan migrants in Germany, distress levels related to acculturation correlated significantly (r = 0.29; p < 0.05) with alcohol use severity [14]. A similar pattern was observed in patients with psoriasis, where problematic alcohol use was associated with distress components such as anxiety and worry [15].

Psychological distress is typically assessed using psychometric scales. A widely used family of assessment tools is based on the Hopkins Symptom Checklist (HSCL-58), consisting of 58 items [6][16], later expanded into the 90-item Symptom Checklist (SCL-90), which is validated for use in Russian-speaking populations [17]. Shorter versions, such as the Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI), the 25-item SCL-25, the 10-item SCL-10, the 5-item SCL-5, and other scales, gained broad application as convenient, psychometrically sound tools for assessing distress (particularly anxiety and depression) across various clinical settings [6][18–20].

To our knowledge, no studies simultaneously examine psychological distress and alcohol use in the context of emergency admission to somatic care among the Russian population, highlighting the need for research in this field.

Objective: to assess (using the SCL-5 screening questionnaire) the prevalence of psychological distress in relation to alcohol consumption, socio-demographic factors, and selected clinical characteristics among somatic patients admitted on an emergency basis to a multidisciplinary city hospital.

Materials and methods

The present study is based on data collected within the framework of a Norwegian-Russian observational, cross-sectional study conducted by Oslo University Hospital in collaboration with the Moscow Research and Practical Centre for Narcology, Moscow Department of Health.

Data was collected in 2016–2017 at V.P. Demikhov City Clinical Hospital, Moscow Department of Health. The study included patients with somatic diseases who were admitted on an emergency basis to the departments of general medicine, pulmonology, neurology, and non-interventional cardiology.

Psychological distress was assessed using the SCL-5 questionnaire, a screening instrument consisting of five items (three assessing depression and two assessing anxiety) derived from the full version of the SCL-90 [21]. SCL-5 scores were used both as a continuous variable and as a dichotomous variable, with a cut-off value of >2 indicating mental distress; this threshold has high correlation, good sensitivity, specificity, and predictive value [20][21]. The SCL-90 and its shorter forms containing the SCL-5 items were translated into Russian and validated [17][22][23]. The SCL-5 assesses symptoms experienced during the preceding 14 days (instructions: Please read each question carefully and mark the feelings that have bothered you over the past 14 days), namely: “Feeling fearful”, “Nervousness or internal shakiness”, “Feeling hopeless about the future”, “Feeling blue”, and “Worrying too much about things”. Responses are rated on a four-point Likert scale (1 – not at all, 2 – a little, 3 – quite a bit, 4 – extremely).

A description of the other measurement instrument (AUDIT-4 [24][25]), inclusion and exclusion criteria, general sample characteristics, alcohol consumption patterns, and ethical considerations were presented in earlier publications [26–30].

Only the primary diagnosis that led to the patient’s hospitalization was considered. From the total sample of 3009 patients, 14 cases were excluded due to incomplete questionnaires (five patients – AUDIT-4 only, six – SCL-5 only, and one both AUDIT-4 and SCL-5).

All patients were divided into four groups according to the profile of medical care provided. In some cases, the care profile did not match the admitting department.

The study was approved by the local ethics committee of the Moscow Research and Practical Centre for Narcology, Moscow Department of Health (Protocol No. 04/2016, dated 27 September 2016).

This paper was prepared in accordance with the STROBE statement (Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology) checklist for cross-sectional studies.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics, version 25.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Categorical variables are presented as absolute numbers and percentages; confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated using E.B. Wilson’s method where appropriate. Associations between categorical variables were assessed using Pearson’s χ² test; for 2×2 contingency tables, Yates’ continuity correction was applied. When the expected frequency in any cell was less than 5, Fisher’s exact test was used. For larger contingency tables, if ≥20% of cells had expected frequencies below 5, the Monte Carlo method was applied. When Pearson’s χ² test indicated statistically significant differences, post hoc pairwise comparisons were conducted with Bonferroni correction, and adjusted p-values were calculated for each comparison. Effect sizes were reported as Cramer’s V for nominal and categorical variables, Kendall’s τ<sub>c</sub> for ordinal variables in rectangular contingency tables, and Kendall’s τ<sub>b</sub> for ordinal variables in square contingency tables.

The distribution of continuous variables was assessed using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test with Lilliefors’ correction. All quantitative variables demonstrated non-normal distributions. Therefore, continuous data are presented as median values with interquartile ranges.

Binary logistic regression was used to examine the influence of predictors on the dependent variable and to control for potential confounders. Nagelkerke’s R² was reported as a measure of effect size.

Population Description

The gender distribution was 47.1% men and 52.9% women; the age distribution was 18–40 years (17.5%), 41–60 years (30.7%), 61–70 years (24.7%), and ≥71 years (27.1%). Married or cohabiting individuals accounted for 48.5%; widowed for 26.9%; unmarried or divorced for 11.4% and 13.2%. Economically active respondents (working or studying) made up 29.2%, while economically inactive (unemployed, disabled) accounted for 16.3%. Pensioners comprised 53.9% of the sample.

Results

The proportion of individuals experiencing psychological distress (SCL-5 > 2 points) was 7.9%. Spearman’s rank correlation showed no statistically significant correlation between AUDIT-4 and SCL-5 scores (ρ = -0.025, p = 0.167).

When diagnosing psychological distress via SCL-5, the number of women scoring above two points exceeded that of men: 9.1% versus 6.6% (Table 1).

Psychological distress was observed in 9.0% of cases in the 18–40 age group and 8.7% in the 41–60 age group. The smallest proportions were found in the 61–70 and ≥71 age groups – 6.8% and 7.4%, respectively; however, these differences were not statistically significant.

Among patients with different marital statuses, the highest proportion of those scoring above two points on the SCL-5 was among the divorced and widowed – 13.1% and 10.3%, respectively. The lowest proportions were among those married (5.5%) and single (6.5%).

Post-hoc comparisons (Bonferroni test) revealed statistically significant differences between the following groups: married vs divorced; married vs widowed; and divorced vs single (Table 3).

The effect size indicated a weak strength of association.

The impact of employment status on distress showed the highest proportion of distressed individuals among the inactive group – 7.9%. Patients in the active and pensioner groups scoring above two points on the SCL-5 comprised 7.0% and 7.6%, respectively.

Post-hoc comparisons (Bonferroni test) showed no statistically significant differences between groups: active vs pensioners (p = 0.700/corrected p = 1.000; Cramer’s V = 0.009); inactive vs pensioners (p = 0.035/corrected p < 0.105; Cramer’s V = 0.048); active vs inactive (p = 0.025/corrected p = 0.075; Cramer’s V = 0.063).

Statistically significant differences were found among those who reported alcohol consumption within 24 hours prior to hospitalization (12.6% were in psychological distress), compared to 7.6% among those who did not report alcohol use, with a small effect size.

A higher proportion of psychological distress was observed among those with harmful alcohol consumption patterns (AUDIT-4 ≥ 5 for women/7 for men) – 10.8%, versus 7.2% among those with lower consumption levels. As in previous comparisons, the effect size was low.

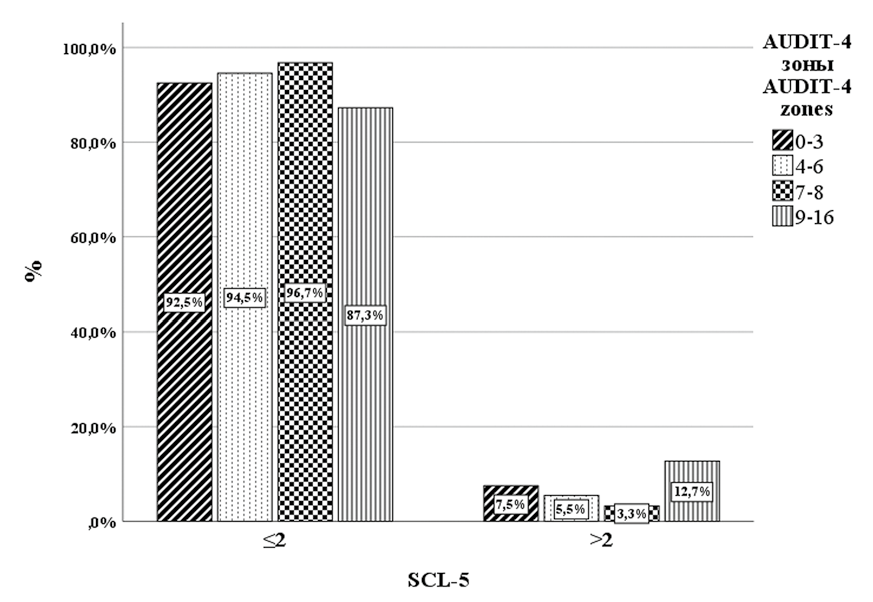

Somewhat unexpected results were found in the distribution of patients in psychological distress across AUDIT-4 categories. For clarity, in addition to Table 1, data are presented in Figure 1, demonstrating that the highest proportion of patients with psychological distress (SCL-5 > 2) was in the fourth AUDIT-4 category (9–16 points), corresponding to risky alcohol consumption and possible alcohol dependence (12.7%), and also among patients in the first AUDIT-4 category (0–3 points), representing low-risk or non-drinkers (7–5%).

Patients in the second AUDIT-4 category (4–6 points), corresponding to alcohol consumption above low-risk levels, exhibited psychological distress in 5.5% of cases. Unexpectedly, only 3.3% of patients in the third AUDIT-4 category (7–8 points), representing hazardous alcohol use, showed psychological distress.

Post-hoc Bonferroni tests indicated that the fourth AUDIT-4 category – “Risky alcohol use and possible alcohol dependence” (9–16 points) – differed significantly in the proportion of individuals with psychological distress compared to the other three categories. However, effect size estimates (Τ-b Kendall’s tau) suggested a negligible or weak positive association between these variables (Table 3). No statistically significant differences were found between the first, second, and third categories.

The highest prevalence of psychological distress was observed in the “Therapeutic profile and diagnostic patients” group (10.2%), followed by the “Cardiology profile” group (9.2%). The lowest rates were found in the “Neurology profile” and “Pulmonology profile” groups (5.7% and 7.5%, respectively).

Bonferroni post-hoc comparisons revealed that patients in the “Pulmonology profile” group differed significantly from those in the “Cardiology” and “Therapeutic and diagnostic” groups. Nevertheless, the association strength, as measured by Cramér’s V, was minimal (Table 4).

To assess the influence of socio-demographic factors, medical care profiles, and alcohol consumption on psychological distress while controlling for confounders, a binary logistic regression analysis was conducted (Table 5).

The dichotomized SCL-5 score (≤ 2/> 2) was chosen as the outcome variable. The predictors included the following variables: sex (male, female); age group (18–40, 41–60, 61–70, and ≥ 71 years); marital status (married/cohabiting, divorced, widowed, single); employment status (active, inactive, retired); alcohol consumption within 24 hours prior to hospitalization (yes, no); AUDIT-4 risk categories (four categories); and medical care profiles (“Neurological profile”, “Cardiological profile”, “Pulmonological profile”, and “Therapeutic and diagnostic patients” profile).

According to the data presented in Table 5, the age groups 61–70 years (OR = 0.472; 95% CI: 0.257–0.868; p = 0.016) and ≥ 71 years (OR = 0.395; 95% CI: 0.205–0.759; p = 0.005) were negatively associated with an SCL-5 score > 2, compared to the 18–40 years reference group. Positive associations with an SCL-5 score > 2 were found among patients who reported their marital status as divorced (OR = 2.289; 95% CI: 1.564–3.351; p < 0.001) and widowed (OR = 2.319; 95% CI: 1.561–3.446; p < 0.001), compared to those married or cohabiting. Female sex was also positively associated with SCL-5 > 2 compared to males (OR = 1.410; 95% CI: 0.998–1.982; p = 0.052), although this result was borderline significant.

Таблица / Table 1

Распределение переменной SCL-5 дихотомной в зависимости от социально-демографических показателей, результатов тестирования AUDIT-4 и профиля оказания медицинской помощи

Distribution of SCL-5 dichotomous variable according to socio-demographic indicators, AUDIT-4 test results and profile of care delivery

|

Переменная / Variable |

SCL-5 ≤2 баллов / SCL-5 ≤2 score N (%) |

SCL-5 > 2 баллов / SCL-5 > 2 score N (%) |

Результаты статистической обработки / Statistical processing results |

|

Пол / Gender |

|||

|

Мужской / Male |

1314 (93,4) |

93 (6,6) |

χ2 = 6,186; df = 1; p = 0,016; V Крамера / Cramer’s V = 0,045 |

|

Женский / Female |

1444 (90,9) |

144 (9,1) |

|

|

Возрастная группа / Age Group |

|

||

|

18–40 |

478 (91,0) |

47 (9,0) |

χ2 = 3,269; df = 3; p = 0,352; Τ-с Кендалла / Kendall τ-c = - 0,016 |

|

41–60 |

837 (91,3) |

80 (8,7) |

|

|

61–70 |

689 (93,2) |

50 (6,8) |

|

|

≥71 |

754 (92,6) |

60 (7,4) |

|

|

Семейное положение / Marital status |

|||

|

Женат/замужем/ гражданский брак / Married / living with partner |

1370 (94,5) |

80 (5,5) |

χ2 = 33,212; df = 3; p < 0,001; V Крамера / Cramer’s V = 0,105 |

|

Разведен/разведена / Divorced |

345 (86,9) |

52 (13,1) |

|

|

Вдовец/вдова / Widowed |

725 (89,7) |

83 (10,3) |

|

|

Неженат/не замужем / Single |

318 (93,5) |

22 (6,5) |

|

|

Занятость* / Occupation |

|||

|

Активен / Active |

830 (92,9) |

63 (7,1) |

χ2 = 6,365; df = 2; p = 0,041; V Крамера / Cramer’s V = 0,046 |

|

Неактивен / Not active |

434 (89,3) |

52 (10,7) |

|

|

Пенсионер / Retired |

1493 (92,4) |

122 (7,6) |

|

|

Потребление алкоголя 24 часа / Alcohol consumption, last 24 hours |

|||

|

Нет / No |

2560 (92,4) |

210 (7,6) |

χ2 = 5,576; df = 1; p = 0,026; V Крамера / Cramer’s V = 0,043 |

|

Да / Yes |

198 (88,0) |

27 (12,0) |

|

|

AUDIT-4 дихотомный / AUDIT-4 Dichotomous |

|

||

|

< 5(ж) (f) / 7(м) (m) |

2248 (92,8) |

175 (7,2) |

χ2 = 8,307; df = 1; p = 0,005; Τ-b Кендалла / Kendall τ-b = 0,053 |

|

≥ 5(ж) (f) /7 (м) (m) |

510 (89,2) |

62 (10,8) |

|

|

AUDIT-4, зоны / AUDIT-4 zones |

|

||

|

Низкий риск или воздержание (0–3 балла) / Low risk or abstinence (0–3 points) |

2044 (92,5) |

166 (7,5) |

χ2 = 16,652; df = 3; p < 0,001; Τ-с Кендалла / Kendall τ-c = - 0,017 |

|

Превышение уровня низкого риска (4–6 баллов) / Exceeding the low risk level (4–6 points) |

225 (94,5) |

13 (5,5) |

|

|

Опасное потребление алкоголя (7–8 баллов) / Hazardous alcohol consumption (7–8 points) |

119 (96,7) |

4 (3,3) |

|

|

Рискованное употребление алкоголя (9–16 баллов) / Risky alcohol consumption (9-16 points) |

370 (87,3) |

54 (12,7) |

|

|

Профиль оказания медицинской помощи / Profile of medical care |

|

||

|

Неврологический профиль / Neurological profile |

688 (92,5) |

56 (7,5) |

χ2 = 11,980; df = 3; p = 0,007; V Крамера / Cramer’s V = 0,063 |

|

Кардиологический профиль / Cardiology profile |

719 (90,8) |

73 (9,2) |

|

|

Пульмонологический профиль / Pulmonology profile |

858 (94,3) |

52 (5,7) |

|

|

Терапевтический профиль и диагностические пациенты / Therapeutic profile and diagnostic patients |

493 (89,8) |

56 (10,2) |

|

Таблица / Table 2

Апостериорные множественные сравнения распределения пациентов по результатам тестирования SCL-5* (SCL-5 ≤2/> 2) в зависимости от семейного статуса (тест Бонферрони)

Posterior multiple comparisons of patient distribution according to SCL-5 test results (SCL-5 ≤2/> 2) according to marital status (Bonferroni test)

|

Группа / Group |

Разведен/-на / Divorced

|

Вдова/-ец / Widowed

|

Одинокий/-ая / Single

|

|

P / P скор. / V Крамера / P/Padjusted / Cramer’s V

|

|||

|

Состоит в браке / Married |

<0,001/<0,001/0,121

|

<0,001/<0,001/0,088 |

0,579/1,000/0,016 |

|

Разведен/-на / Divorced

|

|

0,172/1,000/0,042 |

0,004/0,024/0,110 |

|

Вдова/-ец / Widowed |

|

|

0,054/0,324/0,060 |

Рисунок 1. Распределение пациентов по результатам тестирования SCL-5 в зависимости от зон AUDIT-4*

Figure 1. Distribution of patients by SCL-5 test results depending on AUDIT-4 zones*

Примечание: *за 100% принимается количество наблюдений для каждой зоны переменной AUDIT-4.

Note: *the number of observations for each zone of the AUDIT-4 variable is taken as 100%.

Таблица / Table 3

Апостериорные множественные сравнения распределения пациентов по результатам тестирования SCL-5* (SCL-5 ≤2/> 2) в зависимости от зон AUDIT-4 (тест Бонферрони).

Posterior multiple comparisons of patient distribution by SCL-5 test results (SCL-5 ≤2/> 2) according to AUDIT-4 zones (Bonferroni test).

|

Группа / Group |

Потребление превышающие уровень низкого риска (4–6 баллов) / Consumption exceeding low risk level (4–6 points) |

Опасное потребление алкоголя (7–8 баллов) / Hazardous alcohol consumption (7–8 points) |

Рискованное употребление алкоголя и возможная алкогольная зависимость (9–16 баллов) / Risky alcohol consumption and possible dependence (9-16 points) |

|

P/P скор./Τ-b Кендалла / P/Padjusted/ Kendall τ-b

|

|||

|

Низкий риск или воздержание (0–3 балла) / Low risk or abstinence (0–3 points) |

0,306/1,000/-0,023

|

0,112/0,672/-0,037 |

0,001/0,006/0,069 |

|

Потребление превышающие уровень низкого риска (4–6 баллов) / Consumption exceeding the low risk level (4–6 points) |

|

0,498/1,000/-0,049 |

0,005/0,03/0,115 |

|

Опасное потребление алкоголя (7–8 баллов) / Hazardous alcohol consumption (7–8 points) |

|

|

0,005/0,03/0,128 |

Таблица / Table 4

Апостериорные множественные сравнения распределения пациентов по результатам тестирования SCL-5* (SCL-5 ≤2/> 2) в зависимости от профиля оказания медицинской помощи (тест Бонферрони)

Posterior multiple comparisons of patient distribution by SCL-5* test results (SCL-5 ≤2/> 2) according to the profile of health care delivery (Bonferroni test)

|

Группа / Group |

Кардиологический профиль / Cardiology profile |

Пульмонологический профиль / Pulmonology profile |

|

|

P / Pскор. / V Крамера / P / Padjusted / Cramer’s V

|

|||

|

Неврологический профиль / Neurological profile |

0,274/1,000/0,030

|

0,166/0,996/0,036 |

0,112/0,672/0,047 |

|

Кардиологический профиль / Cardiology profile |

|

0,008/0,048/0,067 |

0,607/1,000/0,017 |

|

Пульмонологический профиль / Pulmonology profile |

|

|

0,002/0,012/0,083 |

Таблица / Table 5

Бинарная логистическая регрессия: переменная отклика — SCL-5 дихотомная (SCL-5 ≤2/> 2)*

Binary logistic regression: response variable is SCL-5 dichotomous (SCL-5 ≤2/> 2)*

|

Переменная / Variable |

SCL-5 дихотомная / SCL-5 dichotomous (SCL-5 ≤2/> 2) |

|||

|

Скорректированное ОШ / Adjusted OR |

95% ДИ / CI |

P |

||

|

Пол / Gender |

|

|

|

|

|

Мужчины / Male |

Рефер. / Ref. |

|

|

|

|

Женщины / Female |

1,403 |

0,998 |

1,974 |

0,052 |

|

Возраст / Age |

|

|

|

|

|

18–40 |

Рефер / Ref. |

|

|

|

|

41–60 |

0,682 |

0,444 |

1,046 |

0,079 |

|

61–70 |

0,472 |

0,257 |

0,868 |

0,016 |

|

≥71 |

0,395 |

0,205 |

0,759 |

0,005 |

|

Семейное положение / Marital status |

|

|

|

|

|

Женат/замужем/ гражданский брак / Married / living with partner |

Рефер. / Ref. |

|

|

|

|

Разведён/разведена / Divorced |

2,289 |

1,564 |

3,351 |

<0,001 |

|

Вдовец/вдова / Widowed |

2,319 |

1,561 |

3,446 |

<0,001 |

|

Не женат/не замужем / Single |

0,900 |

0,533 |

1,519 |

0,692 |

|

Занятость / Occupation |

|

|||

|

Активен / Active |

Рефер. / Ref. |

|

|

|

|

Не активен / Not active |

1,293 |

0,866 |

1,930 |

0,209 |

|

Пенсионер / Retired |

1,176 |

0,719 |

1,923 |

0,519 |

|

Алкоголь, последние 24 часа / Alcohol consumption, last 24 hours |

|

|||

|

Нет / No |

Рефер. / Ref./ |

|

|

|

|

Да / Yes |

1,307 |

0,785 |

2,177 |

0,303 |

|

AUDIT-4 |

|

|

|

|

|

1 зона (0–3 балла) / Zone 1 (0–3 points) |

Рефер. / Ref./ |

|

|

|

|

2 зона (4–6 баллов) / Zone 2 (4–6 points) |

0,867 |

0,470 |

1,467 |

0,649 |

|

3 зона (7–8 баллов) / Zone 3 (7–8 points) |

0,419 |

0,148 |

1,029 |

0,102 |

|

4 зона (9–16 баллов) / Zone 4 (9–16 points) |

1,840 |

1,186 |

2,856 |

0,007 |

|

Неврологический профиль / Neurological profile |

Рефер. / Ref. |

|

|

|

|

Кардиологический профиль / Cardiology profile |

1,534 |

1,026 |

2,293 |

0,037 |

|

Пульмонологический профиль / Pulmonology profile |

0,887 |

0,591 |

1,331 |

0,563 |

|

Терапевтический профиль и диагностические пациенты / Therapeutic profile and diagnostic patients |

1,425 |

0,953 |

2,130 |

0,084 |

Примечание: *размер эффекта, определённый как коэффициент детерминации R2-Hэйджелкерка, составил 0,062.

Note: *the effect size, defined as the R2-Nigelkirk coefficient of determination, was 0.062.

Discussion

One unexpected finding in our study was the notably low level of distress among the Russian sample of somatic patients admitted urgently, compared to the Norwegian sample studied concurrently with the same design – 7.9% versus 22.3% [29][30]. The nearly threefold difference is too substantial to ignore and warrants interpretation. One possible explanation lies in the distinct cultural, religious, and socioeconomic contexts of the compared groups. Mosolov et al. (2021) report that Russian psychiatrists often underdiagnose disorders in the ICD-10 F40-F48 block (Neurotic, stress-related, and somatoform disorders), especially anxiety disorders, which, according to surveys by the World Psychiatric Association and WHO [31], are among the most common diagnoses globally. Causes of this underdiagnosis include organizational issues within psychiatry, stigma associated with mental illness, and insufficient diagnostic competencies [32]. A study of Polish primary care patients found that somatic patients tended to avoid discussing psychological and psychiatric problems openly, often providing socially desirable answers and presenting themselves in a more favorable light [33]. It is also argued that in Russia, stigma around mental disorders (driven by low awareness and social factors) frequently leads to underdiagnosis [34]. Conversely, data from N.V. Sklifosovsky Research Institute of Emergency Care indicate that hospitalized patients there experience high distress levels, with 36% showing moderate distress [35], which at first glance seems to contradict our results. The substantially higher distress levels in those urgently hospitalized patients likely reflect their more severe clinical states, as their sample included patients from emergency, toxicology, trauma, surgery, cardiology, neurosurgery, psychosomatic, burn, neurology, and intensive care units. In contrast, our study did not include patients requiring intensive therapy or urgent surgical care.

The higher proportion of women diagnosed with distress aligns with findings from other studies [36]; we interpret this as a specific instance of the broader pattern of gender differences in psychiatric diagnosis. The WHO report Mental Health in Men concludes men are less likely to seek psychiatric help and have higher suicide rates due to sociocultural barriers related to masculinity norms, emotional expression difficulties, and self-regulation challenges [37]. Our binary logistic regression analysis, conducted to control for confounders, confirmed these findings, albeit with borderline statistical significance.

We did not find statistically significant differences in the distribution of psychological distress cases by age in either frequency or regression analyses, despite a tendency for higher diagnosed cases in the 18–40 and ≥71 age groups. However, some studies show a link between psychological distress and chronic conditions, with the strongest association observed in the 18–44 age group [36].

Numerous authors report a higher prevalence of psychological distress among divorced and widowed individuals, both in the general population and among patients with somatic illnesses [9–11], compared to those who are married or in civil partnerships [38]. This fully corresponds to our findings, which remained statistically significant after controlling for confounders. Contrary to the common belief that unmarried individuals are more prone to distress during hospitalization [9], our results align with those of [10], showing that widowhood and divorce are significantly more associated with psychological distress than simply being single. Blekesaune provides an explanation, arguing that transitions between marital statuses (such as divorce or death of a spouse) have a greater impact on psychological distress development than the marital status itself [39].

The impact of employment status on psychological distress in our study confirmed the expected finding that unemployment is directly associated with increased distress [40, 41], compared to individuals who reported being employed (working or studying) or retired. However, the statistical power of our study was insufficient to draw more definitive conclusions.

We observed that the proportion of individuals experiencing psychological distress was 1.57 times higher among those who reported alcohol consumption within 24 hours prior to hospitalization compared to those who did not. Nevertheless, this association was not confirmed in the logistic regression model after adjusting for all variables, rendering these findings difficult to interpret within the framework of the present study, particularly given that respondents’ current state at the time of assessment was not accounted for.

The absence of any significant correlations between SCL-5 and AUDIT-4 scores may indicate a more complex relationship between alcohol consumption and distress symptoms. This complexity is supported by several studies in the field, which suggest the formation of a vicious cycle: alcohol intake temporarily alleviates distress symptoms but subsequently creates a foundation for prolonged alcohol use, leading to addiction [42]. Authors have noted a U- or J-shaped relationship between the intensity of alcohol consumption and distress: high distress levels are observed both among those who abstain or consume alcohol moderately, and among those who consume it heavily [43–45]. Our data confirm this pattern: the proportion of patients with diagnosed distress (SCL-5 > 2) was higher in the first (0–3 points) and fourth (9–16 points) AUDIT-4 categories compared to the second and third categories, with the association between alcohol consumption and distress in our sample demonstrating a J-shaped curve (Figure 1). Logistic regression adjusting for all variables partially confirmed these findings: the fourth AUDIT-4 category was positively associated with SCL-5 scores > 2 compared to the first category. A similar pattern was observed when comparing median SCL-5 scores across AUDIT-4 categories. This trend is supported by research on the relationship between alcohol consumption and psychological distress among individuals with alcohol dependence undergoing treatment, which found that reductions in alcohol use correlated with increased distress levels [46]. This pattern may extend to emergency hospitalization settings, where inpatient admission leads to abrupt restriction of alcohol consumption and, consequently, increased psychological distress, including beyond the context of alcohol withdrawal syndrome and resulting in reduced treatment compliance [47] and worse treatment outcomes [10][48][49].

A longitudinal study of anxiety and somatoform disorders in patients with oncological, cardiovascular, pulmonary, and musculoskeletal diseases, as well as in a healthy control group, established the predominance of anxiety and depressive disorders among patients with respiratory and cardiovascular diseases [8]. Another study on the prevalence of distress and somatic diseases in the general population found associations between diabetes, dyslipidemia, ischemic heart disease, and psychological distress [50]. Our results align with these findings: patients in the “Therapeutic and diagnostic profile” and “Cardiological profile” groups more frequently experienced psychological distress. The elevated distress in the former group may be explained by the inclusion of diagnostic patients with various unclear diagnoses at the time of hospitalization, including oncological cases [51][52], as well as a small number of subacute surgical pathology cases. After controlling for confounders via logistic regression, a statistically significant positive association remained only for the “Cardiological profile” group compared to the “Neurological profile” group.

Conclusion

Our findings align with previous research on the prevalence of psychological distress in patients with somatic illnesses, as well as the J-shaped relationship between alcohol consumption and psychological distress observed in the Russian population. The potential association between psychological distress and abrupt cessation of alcohol intake during emergency hospitalization highlights the importance of targeted medical interventions to support mental health. The relatively low distress levels observed in male patients may reflect limited sensitivity of the SCL-5 tool in this group, underscoring the need to establish gender-specific cutoff scores. These results can inform the development of support programs for stress-related mental health conditions among hospitalized patients. Early identification and treatment of such conditions within primary care settings could enhance patient adherence and improve clinical outcomes. While the SCL-5 proved to be a brief and practical screening instrument for psychological distress, further validation is needed to confirm its effectiveness in the Russian context.

References

1. Harmful use of alcohol, alcohol dependence and mental health conditions: a review of the evidence for their association and integrated treatment approaches. WHO/ EURO:2019-3571-43330-60791

2. Kurygin А.G., Uryvayev V.А. Mental distress in debut and development of somatic diseases. Human Ecology. 2006;(7):42- 46. (In Russ.) eLIBRARY ID: 9202465 EDN: HTJVDP

3. Russ TC, Stamatakis E, Hamer M, Starr JM, Kivimäki M, Batty GD. Association between psychological distress and mortality: individual participant pooled analysis of 10 prospective cohort studies. BMJ. 2012;345:e4933. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.e4933

4. Skogen JC, Bergh S, Stewart R, Knudsen AK, Bjerkeset O. Midlife mental distress and risk for dementia up to 27 years later: the Nord-Trøndelag Health Study (HUNT) in linkage with a dementia registry in Norway. BMC Geriatr. 2015;15:23. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-015-0020-5

5. Mirowsky J, Ross CE. Measurement for a human science. J Health Soc Behav. 2002;43(2):152-170. PMID: 12096697

6. Drapeau A, Marchand A, Beaulieu-Prevost D. Epidemiology of Psychological Distress. Mental Illnesses – Understanding, Prediction and Control. InTech; 2012. https://doi.org/10.5772/30872

7. Georgaca E. Discourse analytic research on mental distress: a critical overview. J Ment Health. 2014;23(2):55-61. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638237.2012.734648

8. Härter M, Baumeister H, Reuter K, Jacobi F, Höfler M, et al. Increased 12-month prevalence rates of mental disorders in patients with chronic somatic diseases. Psychother Psychosom. 2007;76(6):354-360. https://doi.org/10.1159/000107563

9. Tesfa S, Giru BW, Bedada T, Gela D. Mental Distress and Associated Factors Among Hospitalized Medical-Surgical Adult Inpatients in Public Hospitals, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2020: Cross-Sectional Study. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2021;14:1235-1243. https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S319634

10. Alemu WG, Malefiya YD, Bifftu BB. Mental Distress among Patients Admitted in Gondar University Hospital: A Cross Sectional Institution Based Study. Health science journal. 2016; 10(6):480.

11. Faessler L, Perrig-Chiello P, Mueller B, Schuetz P. Psychological distress in medical patients seeking ED care for somatic reasons: results of a systematic literature review. Emerg Med J. 2016;33(8):581-587. https://doi.org/10.1136/emermed-2014-204426

12. Caldwell TM, Rodgers B, Jorm AF, Christensen H, Jacomb PA, et al. Patterns of association between alcohol consumption and symptoms of depression and anxiety in young adults. Addiction. 2002;97(5):583-594. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00092.x

13. Wang J. Young men who do not drink, as well as those who drink heavily, have high levels of depression and distress. Evid Based Ment Health. 2003;6(1):13. https://doi.org/10.1136/ebmh.6.1.13

14. Haasen C, Sinaa M, Reimer J. Alcohol use disorders among Afghan migrants in Germany. Subst Abus. 2008;29(3):65-70. https://doi.org/10.1080/08897070802218828

15. Founta O, Adamzik K, Tobin AM, Kirby B, Hevey D. Psychological Distress, Alexithymia and Alcohol Misuse in Patients with Psoriasis: A Cross-Sectional Study. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2019;26(2):200-219. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10880-018-9580-9

16. Derogatis LR, Lipman RS, Rickels K, Uhlenhuth EH, Covi L. The Hopkins Symptom Checklist (HSCL): a self-report symptom inventory. Behav Sci. 1974;19(1):1-15. https://doi.org/10.1002/bs.3830190102

17. Tarabrina NV. Workshop on the psychology of post-traumatic stress disorder. Sankt-Petersburg: Piter; 2001. (In Russ.)

18. Timman R, Arrindell WA. A very short Symptom Checklist- 90-R version for routine outcome monitoring in psychotherapy; The SCL-3/7. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2022;145(4):397-411. https://doi.org/10.1111/acps.13396

19. Andersson HW, Nordfjærn T, Mosti MP. The relationship between the Hopkins symptom checklist-10 and diagnoses of anxiety and depression among inpatients with substance use disorders. Nord J Psychiatry. 2024;78(4):319-327. https://doi.org/10.1080/08039488.2024.2323124

20. Strand BH, Dalgard OS, Tambs K, Rognerud M. Measuring the mental health status of the Norwegian population: a comparison of the instruments SCL-25, SCL-10, SCL-5 and MHI- 5 (SF-36). Nord J Psychiatry. 2003;57(2):113-118. https://doi.org/10.1080/08039480310000932

21. Tambs K, Moum T. How well can a few questionnaire items indicate anxiety and depression? Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1993;87(5):364-367. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0447.1993.tb03388.x

22. Dembickij SS. Constructing and validating the SCL-9-NR sociological test. Journal of Sociology. 2018;24(3):8-31. (In Russ.) https://doi.org/10.19181/socjour.2018.24.3.5991

23. Zolotareva AA. Russian-language adaptation of the Symptom Checklist-K-9. Siberian Journal of Psychology. 2023;(89):105- 115. (In Russ.) https://doi.org/10.17223/17267080/89/6

24. Babor T, Higgins-Biddle J, Saunders J, Monteiro M. The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test. Guidelines for Use in Primary Care. WHO, 2001.

25. Gual A, Segura L, Contel M, Heather N, Colom J. Audit-3 and audit-4: effectiveness of two short forms of the alcohol use disorders identification test. Alcohol Alcohol. 2002;37(6):591-596. https://doi.org/10.1093/alcalc/37.6.591

26. Kabashi S, Vindenes V, Bryun EA, Koshkina EA, Nadezhdin AV, et al. Harmful alcohol use among acutely ill hospitalized medical patients in Oslo and Moscow: A cross-sectional study. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2019;204:107588. Erratum in: Drug Alcohol Depend. 2020;213:108073. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2019.107588

27. Nadezhdin AV, Tetenova EYu, Kolgashkin AYu, Petuhov AE, Davydova EN, et al. A cross-sectional study of harmful alcohol consumption in acutely ill neurological patients of a general hospital. Medicina. 2023;11(1):77-109. (In Russ.) https://doi.org/10.29234/2308-9113-2023-11-1-77-109

28. Nadezhdin AV, Tetenova EYu, Petuhov AE, Davydova EN. Cross-Sectional Study of Harmful Alcohol Use Among Acutely Ill Cardiac Patients of a Multidisciplinary Clinic. Medicina. 2024;12(2):90-113. (In Russ.) https://doi.org/10.29234/2308-9113-2024-12-2-90-113

29. Kabashi S, Vindenes V, Bryun EA, Koshkina EA, Nadezhdin AV. Corrigendum to "Harmful alcohol use among acutely ill hospitalized medical patients in Oslo and Moscow: A cross-sectional study" [Drug Alcohol Depend. 204 (2019) 107588]. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2020;213:108073. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2020.108073

30. Gamboa D, Jørgenrud B, Bryun EA, Vindenes V, Koshkina EA, et al. Prevalence of psychoactive substance use among acutely hospitalised patients in Oslo and Moscow: a cross-sectional, observational study. BMJ Open. 2020;10(9):e032572. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2019-032572

31. Reed GM, Mendonça Correia J, Esparza P, Saxena S, Maj M. The WPA-WHO Global Survey of Psychiatrists' Attitudes Towards Mental Disorders Classification. World Psychiatry. 2011;10(2):118-131. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2051-5545.2011.tb00034.x

32. Mosolov SN, Martynikhin IA, Syunyakov TS, Galankin TL, Neznanov NG. Incidence of the Diagnosis of Anxiety Disorders in the Russian Federation: Results of a Web-Based Survey of Psychiatrists. Neurol Ther. 2021;10(2):971-984. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40120-021-00277-w

33. Biała M, Piotrowski P, Kurpas D, Kiejna A, Steciwko A, et al. Psychiatric symptomatology and personality in a population of primary care patients. Ann Agric Environ Med. 2014;21(2):344-348. https://doi.org/10.5604/1232-1966.1108602

34. 34 Pyzhova O.V., Chasovskikh E.E. The problem of stigmatization of mental disorders in Russia. Innova. 2024;10(1):47-50. (In Russ.) https://doi.org/10.21626/innova/2024.1/04

35. Kholmogorova A.B., Subotich M.I., Rakhmanina A.A., Borisonik E.V., Roy A.P., et al. The Experienced Level of Stress and Anxiety in Patients of a Multidisciplinary Medical Center. Russian Sklifosovsky Journal "Emergency Medical Care". 2019;8(4):384-390. (In Russ.) https://doi.org/10.23934/2223-9022-2019-8-4-384-390

36. Liao B, Xu D, Tan Y, Chen X, Cai S. Association of mental distress with chronic diseases in 1.9 million individuals: A population-based cross-sectional study. J Psychosom Res. 2022;162:111040. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2022.111040

37. Gough B, Novikova I. Mental health, men and culture: how do sociocultural constructions of masculinities relate to men’s mental health help-seeking behaviour in the WHO European Region? Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe; 2020.

38. Joutsenniemi K, Martelin T, Martikainen P, Pirkola S, Koskinen S. Living arrangements and mental health in Finland. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2006;60(6):468-475. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.2005.040741

39. Blekesaune M. Partnership Transitions and Mental Distress: Investigating Temporal Order. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2008;70(4):879-890. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2008.00533.x

40. Brown DW, Balluz LS, Ford ES, Giles WH, Strine TW, et al. Associations between short- and long-term unemployment and frequent mental distress among a national sample of men and women. J Occup Environ Med. 2003;45(11):1159-1166. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.jom.0000094994.09655.0f

41. Thomas C, Benzeval M, Stansfeld SA. Employment transitions and mental health: an analysis from the British household panel survey. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2005;59(3):243-249. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.2004.019778

42. Walter M, Dammann G, Wiesbeck GA, Klapp BF. Psychosozialer Stress und Alkoholkonsum: Wechselwirkungen, Krankheitsprozess und Interventionsmöglichkeiten [Psychosocial stress and alcohol consumption: interrelations, consequences and interventions]. Fortschr Neurol Psychiatr. 2005;73(9):517-525. (In German). https://doi.org/10.1055/s-2004-830273

43. Marchand A, Demers A, Durand P, Simard M. The moderating effect of alcohol intake on the relationship between work strains and psychological distress. J Stud Alcohol. 2003;64(3):419-427. https://doi.org/10.15288/jsa.2003.64.419

44. Rodgers B, Korten AE, Jorm AF, Jacomb PA, Christensen H, Henderson AS. Non-linear relationships in associations of depression and anxiety with alcohol use. Psychol Med. 2000;30(2):421-432. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0033291799001865

45. Alati R, Kinner S, Najman JM, Fowler G, Watt K, Green D. Gender differences in the relationships between alcohol, tobacco and mental health in patients attending an emergency department. Alcohol Alcohol. 2004;39(5):463-469. https://doi.org/10.1093/alcalc/agh080

46. Levine JA, Gius BK, Boghdadi G, Connors GJ, Maisto SA, Schlauch RC. Reductions in Drinking Predict Increased Distress: Between- and Within-Person Associations between Alcohol Use and Psychological Distress During and Following Treatment. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2020;44(11):2326-2335. https://doi.org/10.1111/acer.14462

47. Torvik FA, Rognmo K, Tambs K. Alcohol use and mental distress as predictors of non-response in a general population health survey: the HUNT study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2012;47(5):805-816. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-011-0387-3

48. Chiaie RD, Iannucci G, Paroli M, Salviati M, Caredda M, et al. Symptomatic subsyndromal depression in hospitalized hypertensive patients. J Affect Disord. 2011;135(1-3):168-176. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2011.07.008

49. Ferketich AK, Binkley PF. Psychological distress and cardiovascular disease: results from the 2002 National Health Interview Survey. Eur Heart J. 2005;26(18):1923-1929. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehi329

50. Wiltink J, Beutel ME, Till Y, Ojeda FM, Wild PS, et al. Prevalence of distress, comorbid conditions and well being in the general population. J Affect Disord. 2011;130(3):429-437. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2010.10.041

51. Nakaya N, Kogure M, Saito-Nakaya K, Tomata Y, Sone T, et al. The association between self-reported history of physical diseases and psychological distress in a community-dwelling Japanese population: the Ohsaki Cohort 2006 Study. Eur J Public Health. 2014;24(1):45-49. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckt017

52. Keller M, Sommerfeldt S, Fischer C, Knight L, Riesbeck M, et al. Recognition of distress and psychiatric morbidity in cancer patients: a multi-method approach. Ann Oncol. 2004;15(8):1243-1249. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdh318

About the Authors

A. V. NadezhdinRussian Federation

Alexey V. Nadezhdin, Cand. Sci. (Med.), Assistant Professor, Department of Narcology

Moscow

Competing Interests:

Authors declare no conflict of interest

E. J. Tetenova

Russian Federation

Elena J. Tetenova, Cand. Sci. (Med.), Assistant Professor, Department of Narcology

Moscow

Competing Interests:

Authors declare no conflict of interest

Review

For citations:

Nadezhdin A.V., Tetenova E.J. Screening diagnosis of mental distress and alcohol consumption in acutely ill somatic patients. Medical Herald of the South of Russia. 2025;16(2):43-54. (In Russ.) https://doi.org/10.21886/2219-8075-2025-16-2-43-54