Scroll to:

Clinical observation of early prenatal diagnosis of the coronary of hypospadias

https://doi.org/10.21886/2219-8075-2023-14-4-89-95

Abstract

Hypospadias is one of the most common congenital malformations of the male external genitalia and urethra, the main manifestation of which is meatus dystopia. There is a steady increase in the frequency of its occurrence in many countries of the world. Hypospadias have various forms of severity, which significantly affects the patient's management tactics, the volume of surgical treatment and the further prognosis for the boy's life. The article describes a case of early prenatal diagnosis of the coronary form of hypospadias in the fetus at 15 weeks of gestation, followed by postnatal verification of the diagnosis. The possibilities of echography in the early detection of distal forms of hypospadias using an integrated approach in the assessment of external genitalia in a male fetus are shown. This complex of hypospadias markers includes an assessment of the size of the penis, the presence of a curvature of its body, the shape of the head of the penis and the presence of signs of cleavage of the foreskin, which are manifested by its rounding. The ineffectiveness of the long-used «tulip» sign for the early diagnosis of distal forms of hypospadias has been demonstrated. The comparison of the echographic picture of the structure of the genitals in normal and hypospadias at 12 and 15 weeks of pregnancy was carried out.

For citations:

Tyo S.A., Turkina O.S. Clinical observation of early prenatal diagnosis of the coronary of hypospadias. Medical Herald of the South of Russia. 2023;14(4):89-95. (In Russ.) https://doi.org/10.21886/2219-8075-2023-14-4-89-95

Introduction

Hypospadias (derived from the Greek words hypo (under, below) and spadon (fissure, rent); syn. “urethral opening beneath the penis”) is the most common congenital malformation of the male external genitalia and urethra. It is characterized by the displacement of the urethral meatus to the ventral side of the penis. Hypospadias is often associated with penile curvature, cleft glans, and hooded foreskin with deficient skin on the ventral side of the penis. This can cause problems with urination, sexual function, fertility, and mental health [1][2][3].

The incidence of hypospadias ranges from 0.2 to 4.1 cases per 1000 newborn boys. However, in recent years, there have been reports that the prevalence of hypospadias has been increasing [4].

Hypospadias is a multifactorial disease. Its main causes are thought to be various genetic defects and chemical exposures, including medications taken during early pregnancy. Various environmental factors may also contribute to higher incidence rates of hypospadias in certain populations [1][5‒8].

The pathogenesis of hypospadias is primarily based on 5α-reductase deficiency leading to an impaired conversion of testosterone to its active metabolite dihydrotestosterone (DHT), which is essential for the development of male external genitalia. The expression of functional androgen receptors may play a causative role in the development of hypospadias. However, the occurrence of mild and moderate forms cannot be explained by these mechanisms1 [1].

Current approaches to classifying hypospadias severity are based on the site of the abnormal urethral meatus and have no fundamental difference (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Classification of hypospadias [6].

In the late 1970s, hypospadias was generally recognized as an isolated condition, but up to 40% of children had various associated urogenital anomalies and 7–10% had extragenital malformations [9].

Hypospadias is more commonly associated with cryptorchidism, inguinal hernias, upper urinary tract anomalies, anorectal malformations, congenital heart defects, and facial clefts [4][10].

The importance of the prenatal diagnosis of hypospadias has been also demonstrated by the search on the Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM), an international online catalog of human genes and genetic disorders. More than 300 different syndromes and gene mutations were found to be clinically associated with hypospadias, confirming the multifactorial nature of this condition.

Cases of familial hypospadias inherited in an autosomal dominant or X-linked pattern have also been described. In these families, the chance of having a subsequent child with hypospadias is 14%. The prevalence of hypospadias in fathers of male children with hypospadias ranges between 4% and 10% [11].

One of the first reports of prenatal diagnosis of hypospadias was published by Hogdall in 1989. A male fetus at 19–20 weeks was found to have Opitz syndrome by ultrasonographic demonstration of hypertelorism and hypospadias with a shortened, curved penis [12].

The literature review shows that prenatal diagnosis of hypospadias has been successful for years. However, it is not usually made until 20 weeks of gestation, and the majority of reported cases were identified during the third trimester of pregnancy. Hypospadias diagnosis in the early second trimester of pregnancy has been reported since the mid-1990s [13][14].

This article presents a detailed clinical case report on the prenatal diagnosis of coronal hypospadias at 15 weeks of pregnancy.

Materials and Methods

The patient was a 37-year-old septigravida E., secundiparous with 4 abortions. The spouses were in good health and had no significant family history. They were in an exogamous marriage and did not face any occupational health hazards. Additionally, their older children were also healthy. The combined first trimester screening test performed on schedule at the local antenatal clinic showed low risks for chromosomal abnormalities and other pregnancy complications. The fetal anatomy and life-support system were normal, and no signs of congenital malformations were found. The ultrasound imaging identified the fetus as a female. Because the patient was 37 years old, she was offered noninvasive prenatal testing (NIPT), which showed the male fetus to be at high risk for Klinefelter's syndrome. This prompted an unscheduled ultrasound at 15 weeks of gestation, primarily for gender identification.

The examination was performed using Samsung Medison Accuvix A30 equipped with a Samsung V4-8 Transabdominal 3D Curved-Array Probe.

Results

The ultrasound revealed a live male fetus. Fetal biometric parameters were normal for the gestational age. The placenta, umbilical cord, and amniotic fluid were sonographically normal. The fetal external genitalia were clearly male, however not typical for the gestational age due to the curved and shortened penis, which was located ventrally close to the scrotum (Figures 2, 3, 4, 5). No other anatomical findings or malformations were observed in the fetus.

Figure 2. Pregnancy, 15 weeks.

External genitalia of a male fetus with a coronal of hypospadias (sagittal section).

Figure 3. Pregnancy, 15 weeks.

The external genitalia of the male fetus are normal (sagittal section).

Figure 4. Pregnancy, 15 weeks.

External genitalia of a male fetus with a coronal of hypospadias (axial section).

Figure 5. Pregnancy, 15 weeks.

The external genitalia of the male fetus are normal (axial section).

The ultrasound findings suggested an anterior (distal) or middle (midshaft) hypospadias, ruling out extremely severe posterior forms. During the discussion with the parents, it was emphasized that the ultrasound was inconclusive regarding the gestational age and external genitalia morphology. The discussion also covered further diagnostic measures and prognosis once the diagnosis was confirmed.

Based on the high risk for Klinefelter syndrome indicated by the NIPT and the sonographic findings of external genitalia malformations, the patient was advised to consult a genetics professional to determine the necessity of invasive prenatal diagnosis.

At 16–17 weeks of gestation, amniocentesis was performed for cytogenetic testing and chromosomal microarray (CMA), which revealed a 46,XY karyotype fetus without chromosomal abnormalities.

A follow-up ultrasound was to be scheduled for the second trimester of pregnancy and at 30 weeks to confirm and evaluate the diagnosed changes, better visualize the urethral orifice, trace its pathway, and record urination. However, the patient decided to continue the follow-up at the local clinic. During the antenatal care by phone, the patient reported that the follow-up ultrasound did not confirm or rule out the primary diagnosis.

A live, full-term baby boy (birth weight of 3600 g, length of 53 cm) was born by spontaneous vaginal delivery at home (Figure 6, 7).

Figure 6. External genitalia of a newborn with a coronal of hypospadias (side view).

Figure 7. External genitalia of a newborn with a coronal of hypospadias (bottom view).

Discussion

One of the main sonographic markers of hypospadias is the well-known "tulip sign", which correlates with the severity of the condition. This sign was first reported by Meizner in 2002. In the study of prenatal diagnosis of hypospadias, in six of the seven cases with hypospadias, a severe form of peno-scrotal hypospadias was found. In all six cases, a specific ultrasound feature of the external genitalia was observed in a shape resembling a tulip flower, represented by the ventrally curved penis located between the two scrotal folds [15]. It should be noted that this sign is not always unequivocal and pathognomonic of hypospadias. The variety of classifications and anatomical manifestations of this defect dictates a more detailed ultrasound examination of the external genitalia of the male fetus. The sonographic criteria used to diagnose hypospadias include evaluating the shape and size of the penis, the severity of its curvature, and the morphology of the glans penis and foreskin.

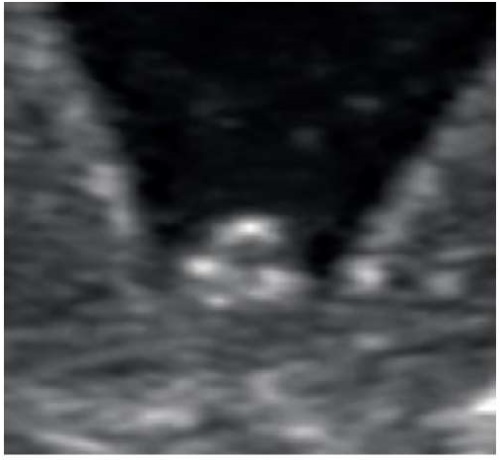

This clinical case presents coronal hypospadias, where the meatus is located in the coronal sulcus of the glans penis. The ultrasound at 15 weeks revealed a curved, shortened penis, which is uncommonly associated with this type of hypospadias. Hypospadias can also be identified by the cleft foreskin, which causes the glans penis to have a "blunt tip" appearance on ultrasound (Figure 8), as opposed to the acorn-shaped glans penis with a normally formed foreskin (Figure 9). This abnormality was clearly observed in this case.

Figure 8. Pregnancy, 15 weeks.

Rounded head of the penis with splitting the foreskin with coronary hypospadias.

Figure 9. Pregnancy, 15 weeks.

The pointed shape of the head without splitting the foreskin.

Prenatal 3D ultrasound has also become extensively used in the diagnosis of hypospadias. Most studies comparing 2D ultrasound and 3D-reconstructed models of the external genitalia in hypospadias have highlighted several advantages. These include better visualization of the relative position of the scrotum and penis, accurate measurement of penis hypoplasia in its abnormal position, and clear demonstration of the abnormalities to parents and pediatric surgeons. It should be noted that these advantages are only available during the latter half of pregnancy for severe posterior forms of hypospadias [16][17].

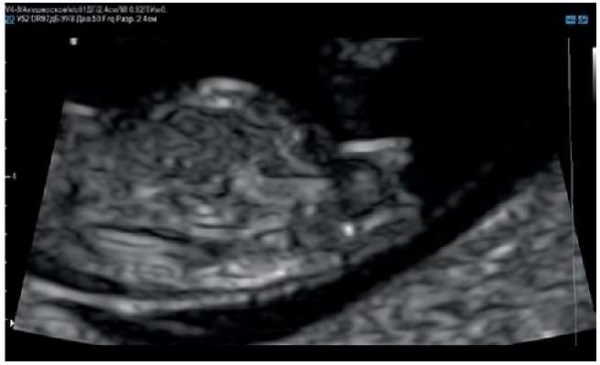

A comparative analysis could not be performed in this case due to spatial limitations in obtaining a sufficient 3D image of the fetus's perineum and external genitalia (Figure 10).

Figure 10. Pregnancy, 15 weeks.

Fetal trunk and lower limbs in three-dimensional echography mode.

This clinical case also demonstrates additional aspects of the prenatal diagnosis of hypospadias. First, fetal gender identification has been known for more than 20 years. The baby's gender can be predicted by ultrasound toward the end of the first trimester by the angle of the genital tubercle to a horizontal measured in the mid-sagittal plane (Figures 11, 12). Correct identification of the fetal gender is most successful after 13 weeks [18].

Figure 11. Pregnancy, 12 weeks. Genital tubercle in a male fetus.

Figure 12. Pregnancy, 12 weeks. Genital tubercle in a female fetus.

In the reported case, first-trimester screening suggested a female fetus, which was not further confirmed. Based on the mechanism of this malformation, most boys with hypospadias are likely to have genital tubercles similar to those of female fetuses at the end of the first trimester (Figure 13).

Figure 13. Pregnancy, 12 weeks.

Genital tubercle in a male fetus with hypospadias.

Second, in recent years, there has been a growing interest in NIPT among both medical professionals and patients. Pregnant women will present with positive NIPTs and the abnormal morphology of the fetal external genitalia by ultrasound more often. Given the high incidence of hypospadias, it is reasonable to focus professional efforts on identifying or excluding hypospadias rather than considering such cases as erroneous fetal gender identification.

Conclusion

Due to the increasing incidence of hypospadias in the population and the variety of its types, prenatal diagnostic specialists may frequently encounter this malformation in their practice. Identifying fetal gender through ultrasound imaging of the external genitalia can be challenging, particularly toward the end of the first trimester and the beginning of the second trimester. Therefore, it is recommended to focus on the size and curvature of the penis, the sonographic morphology of the glans penis and foreskin, rather than being limited to the "tulip sign".

1. Sayedov KM. Surgical management options in proximal hypospadias in children. Extended Abstract of Cand. Sci. (Med.) Dissertation. Moscow, 2014. 24 pages.

References

1. Baranov A.A., Namazova-Baranova L.S., Zorkin S.N., Kovarskii S.L., Menovshchikova L.B., A.K. Faizulin et al. Federal'nye klinicheskie rekomendatsii po okazaniyu meditsinskoi pomoshchi detyam s gipospadiei. 2015. (In Russ.)

2. Holov Sh.I., Kurbanov U.A., Davlatov A.A., Dzhanobilova S.M., Saidov I.S. Modern state of the problem of treatment of patients with hypospadias. Avicenna bulletin. 2017;19(2):254-260. (In Russ.) https://doi.org/10.25005/2074-0581-2017-19-2-254-260

3. van der Horst HJ, de Wall LL. Hypospadias, all there is to know. Eur J Pediatr. 2017;176(4):435-441. Erratum in: Eur J Pediatr. 2017;176(10 ):1443. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00431-017-2864-5

4. Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine (SMFM); Sparks TN. Hypospadias. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2021;225(5):B18-B20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2021.06.045

5. Raghavan R, Romano ME, Karagas MR, Penna FJ. Pharmacologic and Environmental Endocrine Disruptors in the Pathogenesis of Hypospadias: a Review. Curr Environ Health Rep. 2018;5(4):499-511. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40572-018-0214-z

6. Chen MJ, Macias CG, Gunn SK, Dietrich JE, Roth DR, et al. Intrauterine growth restriction and hypospadias: is there a connection? Int J Pediatr Endocrinol. 2014;2014(1):20. https://doi.org/10.1186/1687-9856-2014-20

7. Mattiske DM, Pask AJ. Endocrine disrupting chemicals in the pathogenesis of hypospadias; developmental and toxicological perspectives. Curr Res Toxicol. 2021;2:179-191. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crtox.2021.03.004

8. Gaspari L, Tessier B, Paris F, Bergougnoux A, Hamamah S, et al. Endocrine-Disrupting Chemicals and Disorders of Penile Development in Humans. Sex Dev. 2021;15(1-3):213-228. https://doi.org/10.1159/000517157

9. Shima H, Ikoma F, Terakawa T, Satoh Y, Nagata H, et al. Developmental anomalies associated with hypospadias. J Urol. 1979;122(5):619-21. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0022-5347(17)56527-1

10. W u WH, Chuang JH, Ting YC, Lee SY, Hsieh CS. Developmental anomalies and disabilities associated with hypospadias. J Urol. 2002;168(1):229-32. PMID: 12050549.

11. Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM) MIM Number: 300633 Hypospadia 1, X-linked; HYSP1. Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD2019.

12. Hogdall C, Siegel-Bartelt J, Toi A, Ritchie S. Prenatal diagnosis of Opitz (BBB) syndrome in the second trimester by ultrasound detection of hypospadias and hypertelorism. Prenat Diagn. 1989;9(11):783-93. https://doi.org/10.1002/pd.1970091107

13. Bronshtein M, Riechler A, Zimmer EZ. Prenatal sonographic signs of possible fetal genital anomalies. Prenat Diagn.1995;15(3):215-9. https://doi.org/10.1002/pd.1970150303

14. Sides D, Goldstein RB, Baskin L, Kleiner BC. Prenatal diagnosis of hypospadias. J Ultrasound Med. 1996;15(11):741-6. https://doi.org/10.7863/jum.1996.15.11.741

15. Meizner I, Mashiach R, Shalev J, Efrat Z, Feldberg D. The 'tulip sign': a sonographic clue for in-utero diagnosis of severe hypospadias. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2002;19(3):250-3. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1469-0705.2002.00648.x

16. Iskhakov M.M., Tolkova E.V., Kopytova E.I. Prenatal ultrasound manifestation of hypospadias during the second half of pregnancy using volume ultrasound. Prenatal diagnostics. 2014;13(1):39-44. (In Russ.). eLIBRARY ID: 22597896

17. Li X, Liu A, Zhang Z, An X, Wang S. Prenatal diagnosis of hypospadias with 2-dimensional and 3-dimensional ultrasonography. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):8662. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-45221-z

18. Efrat Z, Akinfenwa OO, Nicolaides KH. First-trimester determination of fetal gender by ultrasound. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 1999;13(5):305-7. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1469-0705.1999.13050305.x

About the Authors

S. A. TyoRussian Federation

Sergey A. Tyo – ultrasound diagnostics in obstetrics and gynecology, candidate of sciences in medicine

Moscow

Competing Interests:

The authors declare no conflict of interest

O. S. Turkina

Russian Federation

Olga S. Turkina – p.h.d., associate professor, department of normal physiology

Moscow

Competing Interests:

The authors declare no conflict of interest

Review

For citations:

Tyo S.A., Turkina O.S. Clinical observation of early prenatal diagnosis of the coronary of hypospadias. Medical Herald of the South of Russia. 2023;14(4):89-95. (In Russ.) https://doi.org/10.21886/2219-8075-2023-14-4-89-95