Scroll to:

The impact of the duration of untreated psychosis on the risk of involuntary hospitalization during the first psychotic episode

https://doi.org/10.21886/2219-8075-2025-16-2-65-74

Abstract

Objective: to assess the effect of untreated psychosis duration on the likelihood of involuntary hospitalization among patients with a first psychotic episode. Materials and methods: a retrospective analysis of data from patients admitted to inpatient treatment between 2020 and 2023 was conducted. Data was collected on the duration from the onset of the psychotic episode until hospitalization, as well as the reasons and circumstances leading to hospitalization, with clinical, psychopathological, and psychometric assessments of the patient's condition. Results: patients whose first episode of psychosis went untreated for more than 3 months were more likely to be hospitalized involuntarily compared to those who received treatment within the first month after symptom onset. Conclusions: the presence of destructive and autoaggressive behaviors, as well as gross psychoproductive symptoms and a high level of psychopathization, along with patient refusal of treatment increased the risk of hospitalization without consent. These findings emphasize the importance of early diagnosis and treatment for psychotic disorders, particularly in the case of a first episode. Early intervention can help reduce the risk of involuntary hospitalization and improve long-term treatment outcomes.

Keywords

For citations:

Chinarev V.A., Malinina E.V. The impact of the duration of untreated psychosis on the risk of involuntary hospitalization during the first psychotic episode. Medical Herald of the South of Russia. 2025;16(2):65-74. (In Russ.) https://doi.org/10.21886/2219-8075-2025-16-2-65-74

Introduction

Schizophrenia spectrum disorders typically manifest in late adolescence, early adulthood, or early mature age, often without timely medical intervention before patients come to the attention of specialists. These disorders frequently follow a recurrent, chronic, and disabling course, impairing professional, family, and social functioning [1]. The first psychotic episode is considered a key stage in the course of schizophrenia, and effective treatment at this stage has a decisive impact on long-term prognosis [2]. Around 70% of individuals with mental disorders do not receive pharmacological treatment [3]. Factors contributing to delayed or absent care include low awareness of mental disorders and their symptoms [4], lack of information on where to seek help, and persistent prejudice and stigma toward psychiatric patients [5].

A prolonged interval between the onset of initial symptoms and the initiation of treatment is linked to poorer clinical outcomes in schizophrenia [6]. Studies reveal that extended treatment delays are associated with more severe positive and negative symptoms [7], lack of sustained remission, reduced global and social functioning [8], higher social anxiety [9], diminished quality of life [10], and structural brain changes, including hippocampal atrophy [11] and other morphological alterations [12]. The duration of untreated psychosis, defined as the period from the first symptoms of a psychotic disorder to the start of pharmacological therapy, is therefore a key modifiable factor influencing the course of the illness [13].

Psychopathological disturbances caused by the prolonged absence of care often necessitate urgent intervention. Clinical presentations leading to involuntary psychiatric hospitalization include aggressive behavior, violence toward others, suicidal tendencies, substance abuse, and a complete lack of insight [14][15]. In these cases, inpatient treatment without consent provides necessary medical care and ensures the safety of both the patient and others [16].

Involuntary hospitalization may be a justified measure [17], contributing to the long-term well-being of patients and their families. However, many patients experience fear [18], psychological trauma, and stigma, which can later lead to refusal of psychiatric care, greater risk of repeated emergency hospitalizations, and restrictive consequences such as social isolation and employment limitations [19][20].

A long-term retrospective study has found that over one-third of patients with schizophrenia fail to adhere to prescribed treatment within a year after discharge, substantially increasing the risk of rehospitalization, self-harm, and reduced quality of life [21]. Involuntary treatment is used when patients refuse therapy and their symptoms pose a threat to their own or public safety. Nonetheless, the issue remains the subject of ethical, clinical, and legal debate and is strictly regulated in Russia. Balancing patient protection with respect for individual rights continuously provokes discussion in the professional community.

Early intervention during the first psychotic episode is crucial for reducing the duration of untreated psychosis and the need for involuntary hospitalization. Evidence shows that timely diagnosis and adequate therapy can markedly improve cognitive and functional outcomes and reduce the risk of relapse and disability [22]. Targeted treatment at the onset of psychopathological symptoms helps lower stigma and overcome barriers to timely care [23]. This approach improves patients’ quality of life and optimizes the use of mental health system resources, preventing excessive costs from prolonged hospital stays and involuntary admissions.

The study aims to examine the relationship between untreated psychosis duration and the likelihood of involuntary hospitalization in patients with a first psychotic episode.

Materials and methods

The study was conducted in 2020–2023 in the Clinical Departments for the First Psychotic Episode at the State Budgetary Healthcare Institution “Chelyabinsk Regional Clinical Specialized Neuropsychiatric Hospital No. 1”, in collaboration with the Department of Psychiatry of the South Ural State Medical University, Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation.

A total of 94 patients (56 men and 38 women) admitted to a psychiatric hospital were examined. The mean age at the time of assessment was 29 years [16; 47]. Of these, 48.9% (n = 46) were hospitalized involuntarily, and 51.1% (n = 48) voluntarily. The mean duration of untreated psychosis was 74 days: 96.7 days for involuntarily hospitalized patients and 53.6 days for voluntary admissions.

Inclusion criteria:

1) Presence of a first psychotic episode (illness duration no more than 5 years and no more than 3 hospitalizations).

2) Psychotic disorder meeting ICD-10 criteria for F20, F23.0, F25, or F23.1.

Exclusion criteria:

1) Psychotic episode induced by psychoactive substance use, including alcohol.

2) Intellectual disability with a Wechsler IQ score below 70.

Ethical approval

All participants provided voluntary informed consent. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of South Ural State Medical University (protocol No. 5, June 10, 2024) and complied with the principles of the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki (revised 1975–2013).

The methodological framework included clinical-anamnestic, clinical-psychopathological, dynamic, and psychometric approaches, using standardized scales: the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) with subscales for positive symptoms (PANSSpos), negative symptoms (PANSSneg), and general psychopathology (PANSSpsy). Scale scores were recorded at admission and on Day 30 of treatment. After stabilization and resolution of prominent psychotic symptoms, experimental-psychological assessment was conducted, including the Leonhard-Smishek Characterological Questionnaire (1970), the Neuroticism and Psychopathy Level Test (1980), and the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for the quantitative evaluation of intellectual functioning.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using Statistica 12. Student’s t-test was applied to assess statistical significance between groups. Pearson’s χ² test was used to assess the independence of categorical variables. Since clinical group data were not normally distributed, nonparametric methods were applied, including the Mann-Whitney U test for both intergroup and intragroup comparisons. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

Results

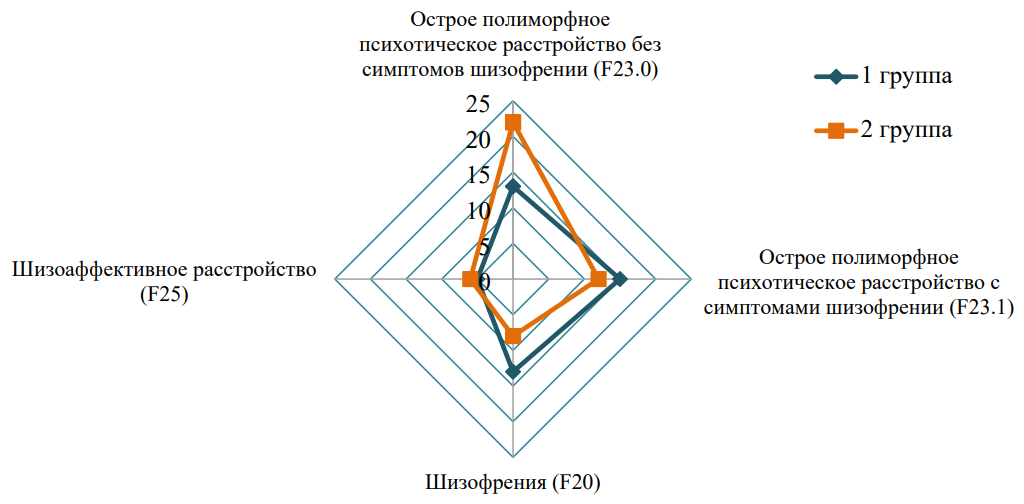

Schizophrenia (F20) was diagnosed in 21 patients (22.3%), schizoaffective disorder (F25) in 11 (11.7%), acute polymorphic psychotic disorder without symptoms of schizophrenia (F23.0) in 35 (37.23%), and acute polymorphic psychotic disorder with symptoms of schizophrenia (F23.1) in 27 (28.7%). The mean age of onset was 29 years [ 16; 47], and the mean illness duration was 1.82 years [ 0.21; 4.8].

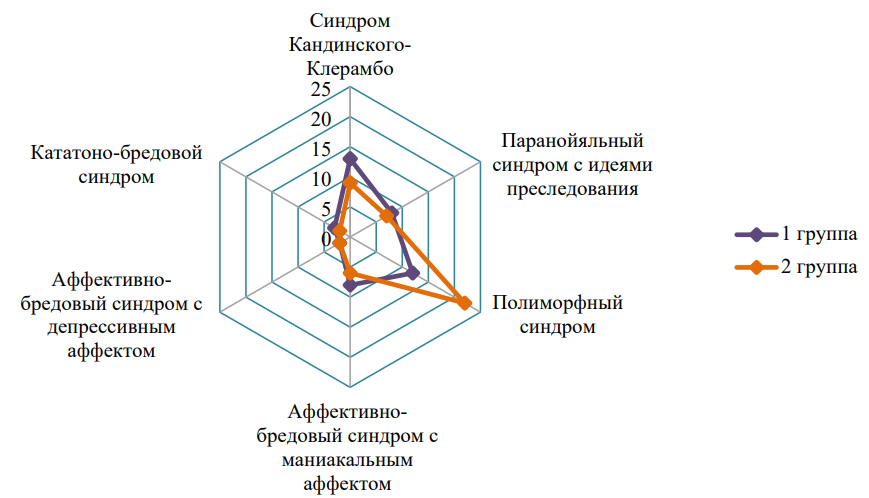

The most frequent syndromes were Kandinsky-Clérambault syndrome (22 patients) and paranoid syndrome with persecutory delusions (15 patients). Polymorphic syndrome was observed in 34 patients, affective-delusional with manic affect in 14, affective-delusional with depressive affect in 4, and catatonic-delusional in 5.

Psychotic symptom severity at presentation ranged from mild to moderate according to PANSS. Significant positive correlations were found between general psychopathological symptoms at admission (p < 0.05) and at day 30 of treatment (p < 0.05). Moderate symptom reduction was observed across PANSS total and all subscales – positive (PANSSpos), negative (PANSSneg), and general psychopathology (PANSSpsy) (all p < 0.05).

The two hospitalization types allowed forming clinical subgroups of patients with the first psychotic episode differing in the duration of untreated psychosis. Group I included involuntarily hospitalized patients; Group II included voluntary admissions. The duration from first symptoms to seeking qualified care, and the type of hospitalization were assessed. Each group contained patients with different nosological diagnoses and varied lengths of untreated psychosis, as well as with or without consent for treatment. Table 1 presents the clinical-psychopathological characteristics of patients with the first psychotic episode. The nosological distribution and syndromal structure in both groups are shown in Figures 1 and 2.

The results of psychometric and experimental-psychological assessments of patients’ conditions (PANSS, the Leonhard-Smishek Characterological Questionnaire, and the Neuroticism and Psychopathy Level Test), with evaluation of dynamics at admission and on the 30th day of treatment, are presented in Table 2. In Group I, the nosological structure was dominated by acute polymorphic psychotic disorder with symptoms of schizophrenia (F23.1) – 32.61% (n = 15), schizophrenia (F20) – 28.26% (n = 13), and acute polymorphic psychotic disorder without symptoms of schizophrenia (F23.0) – 28.26% (n = 13). In contrast, in Group II, the most frequent diagnosis was acute polymorphic psychotic disorder without symptoms of schizophrenia (F23.0) – 45.84% (n = 22), followed by acute polymorphic psychotic disorder with symptoms of schizophrenia (F23.1) – 25.0% (n = 12), and schizophrenia (F20) – 16.67% (n = 8).

Таблица / Table 1

Клинико-психопатологическая характеристика пациентов обеих группах

Clinical, psychopathological and nosological characteristics of patients in two groups

|

Характеристика Characteristic |

Группа 1 Group 1 |

Группа 2 Group 2 |

|

|

Наследственная отягощенность по психическим заболеваниям Hereditary burden of mental illnesses |

Отягощена |

32 (69,56%) |

26 (54,17%) |

|

Не отягощена |

14 (30,43%) |

22 (45,83%) |

|

|

Занятость (трудоустройство) |

Трудоустроен |

26 (56,52%) |

32 (66,67%) |

|

Безработный |

20 (43,48%) |

16 (33,33%) |

|

|

Проживание в семье (браке) |

Проживает в семье |

18 (39,13%)* |

34 (70,83%)* |

|

Проживает вне семьи |

28 (68,87%) |

14 (29,17%) |

|

|

Длительность периода нелеченого психоза |

< 50 дней |

9 (19,56%) |

19 (39,58%) |

|

51-90 дней |

6 (13,04%) |

11 (22,91%) |

|

|

91-150 дней |

13 (28,26%)** |

12 (25,0%)** |

|

|

> 151 дней |

18 (39,13%)** |

6 (12,50%)** |

|

Примечание: *χ² = 3.841 — статистически значимые различия (p<0.05); **χ² = 7.81 — статистически значимые различия (p<0.05).

Note: *χ² = 3.841 — statistically significant differences (p<0.05); **χ² = 7.81 — statistically significant differences (p<0.05).

Рисунок 1. Синдромологический профиль в обеих группах

Figure 1. The syndromological profile in 2 groups

Рисунок 2. Нозологическая характеристика в обех группах

Figure 2. Nosological characteristics in both groups

Таблица / Table 2

Психометрическая, экспериментально-психологическая оценка состояния пациентов (PANSS, характерологический опросник К. Леонгарда-Шмишека, УНП)

Psychometric and experimental psychological assessment of patients’ condition (PANSS, characterological questionnaire of K. Leonhard-Schmieschek characterological questionnaire, UNP)

|

Шкала, средний суммарный балл (ССБ) |

Оценка, по данным обследования пациентов |

|

|

I группа (недобровольный тип госпитализации) |

II группа (добровольный тип госпитализации) |

|

|

PANSS* |

114 [ 104;120,75] |

96,22 [ 91,2;101,25] |

|

Редукция ССБ PANSS, % (p = 0,025)** |

28,41 |

31,21 |

|

PANSSpos* |

32 [ 29;34] |

33 [ 27;35] |

|

Редукция ССБ PANSSpos, % (p = 0,026)** |

35,31 |

39,12 |

|

PANSSneg* |

30 [ 25,25;32] |

21,4 [ 18;23] |

|

Редукция ССБ PANSSneg, % (p = 0,049)** |

33,31 |

34,43 |

|

PANSSpsy* |

36 [ 29;39] |

34 [ 31;39] |

|

Редукция ССБ PANSSpsy, % (p = 0,018)** |

42,12 |

35,84 |

|

Характерологический тип личности n, (%) |

||

|

Гипертимный |

2 (4,35%) |

1 (2,08%) |

|

Возбудимый |

9 (19,6%) |

5 (10,41%) |

|

Эмотивный |

4 (8,69%) |

2 (4,17%) |

|

Педантичный Pedantic |

1 (2,17%) |

5 (10,41%) |

|

Тревожный |

15 (32,6%) |

16 (33,33%) |

|

Циклотимный |

2 (4,35%) |

4 (8,33%) |

|

Демонстративный |

1 (2,17%) |

1 (2,08%) |

|

Неуравновешенный |

3 (6,52%) |

2 (4,17%) |

|

Дистимный |

5 (10,87%) |

9 (18,75%) |

|

Экзальтированный |

4 (8,69%) |

3 (6,25%) |

|

x2=0,8367***, p < 0,05 |

||

|

УНП n, (%) Level of neurotization and psychopatization n, (%) |

||

|

Высокий уровень невротизации |

21 (23,9%) |

18 (37,50%) |

|

Низкий уровень невротизации |

12 (26,1%) |

16 (33,3%) |

|

Высокий уровень психопатизации |

29 (63,04%) |

21 (43,75%) |

|

Низкий уровень психопатизации |

9 (19,56%) |

13 (27,08%) |

|

x2=0,9716***, p < 0,05 |

||

Примечание: *указаны медиана и 25% и 75% квартили, **указаны уровни достоверности р между двумя группами, определенные критерием Манни-Уитни, ***коэффициент критерия Пирсона (x2).

Note: *Median and 25th and 75th percentiles are provided; **Levels of significance (p-values) between two groups, determined by the Mann-Whitney criterion; ***Pearson's chi-square coefficient (x²).

Group I included patients hospitalized involuntarily. The median age was 23 [ 18; 39] years, and the median age of disease onset was 24 [ 18; 39] years. The duration of untreated psychosis (DUP) varied: up to 50 days in 9 (19.56%) cases, 51–90 days in 6 (13.04%) cases, 91–150 days in 13 (28.26%) cases, and more than 151 days in 18 (39.13%) cases. Psychopathologically burdened heredity was noted in 32 (69.56%) patients; 26 (56.52%) were employed; 18 (39.13%) lived with their families.

The clinical picture of Group I was characterized by polymorphic psychotic symptomatology, predominantly pseudohallucinatory experiences in the form of auditory hallucinations, and, in rare cases (n = 3), hallucinations of general sensation. Delusional disorders were often systematized, including ideas of influence, poisoning, and persecution, linked to a perceived real threat to life, as well as the “artificially created” and staged events. In most cases, these delusions were secondary to hallucinatory symptoms. Severe behavioral disturbances – psychomotor agitation with aggression and violence, sometimes transforming the persecuted into the persecutor — were frequently driven by threatening and imperative auditory hallucinations.

Ideational automatisms, as part of Kandinsky-Clérambault syndrome, manifested as feelings of thought insertion and thought broadcasting. Sensory automatisms included sensations of compression and expansion in the chest, and feelings of movement or pressure within the brain. Patients were convinced they were being influenced by special equipment or poisonous substances. At the peak of psychosis, delusions underwent “paraphrenization”, acquiring either an affective coloring (e.g., beliefs in “high” origin, special status, or positive doubles) or a nihilistic form (conviction of internal organ decay). Persistent food refusal, due to delusional beliefs about the absence of digestive organs, led to water-electrolyte and protein-energy imbalances, worsening the patients’ somatic condition. Catatonic excitement was observed, presenting as chaotic and purposeless activity. Elements of sub-stupor were also noted, with slowed motor and speech production, negativism, and altered muscle tone. Suicidal and auto-aggressive behavior reflected a low level of social functioning and lack of support, occurring in Group I patients with moderately expressed psychotic symptoms (per PANSSpos) and subdepressive features. Prolonged DUP, lack of timely help, and social isolation formed a vicious cycle, in which worsening psychotic symptoms heightened the risk of auto-aggression.

Statistical analysis showed significantly higher baseline scores in Group I on the PANSS positive symptom subscale (p < 0.05), as well as greater severity of negative symptoms (PANSSneg), manifested by marked emotional and social withdrawal, reduced speech spontaneity, and stereotyped thinking. Disturbances in the thinking disorder cluster were also significantly higher than in Group II (p < 0.05). Reduction in the total PANSS score after 30 days of therapy was less than 30%.

Assessment of personality traits (the Leonhard-Smishek Characterological Questionnaire, the Neuroticism and Psychopathy Level Test) revealed predominantly anxious traits in 32.6% (n = 15), excitable traits in 19.6% (n = 9), and dysthymic traits in 10.87% (n = 5). The Neuroticism and Psychopathy Level Test showed high levels of neuroticism in 23.9% (n = 21) and high levels of psychopathy in 63.04% (n = 29).

Group II included patients hospitalized voluntarily. The median age was 28 [ 18; 47] years, and the median age of disease onset was 26 [ 18; 47] years. DUP distribution was as follows: up to 50 days – 19 (39.58%) cases, 51–90 days – 11 (22.91%) cases, 91–150 days – 12 (25.0%) cases, and more than 151 days – 6 (12.50%) cases. Psychopathologically burdened heredity was present in 26 (54.17%) patients; 32 (66.67%) were employed; 34 (70.83%) lived with their families.

The clinical presentation was also polymorphic, with persistent affective changes and delusional disorders. The dominant delusional themes were persecution and influence, typically of an interpretative nature, which led to corresponding delusional behavior. Patients actively sought contact with supposed “persecutors”, attempted to leave home, and tried to escape the perceived threat. Hallucinatory disturbances took the form of verbal pseudohallucinations, most often with commenting, dialogic, and less frequently threatening content. In this group, Kandinsky–Clérambault syndrome was limited to persecutory ideas and ideational automatisms. Compared with Group I, Group II patients had significantly lower baseline negative and general psychopathology scores (PANSS, p < 0.05), while productive symptoms (PANSSpos) predominated and showed a significantly greater reduction during treatment (over 39%, p < 0.05). This underscores the effectiveness and timeliness of treatment, as well as its impact on the productive component of psychopathology.

Patients in Group II, who sought medical help at early stages of illness, demonstrated more favorable clinical outcomes. Early diagnosis and prompt treatment contributed to reduced severity of psychotic symptoms, shorter hospital stays, and stable remission with high functional recovery.

Assessment of personality traits revealed the predominance of anxious traits in 33.33% (n = 16), dysthymic traits in 18.7% (n = 9), and excitable and pedantic traits in 10.41% (n = 5) each. The Neuroticism and Psychopathy Level Test revealed high neuroticism in 37.50% (n = 18) and high psychopathy in 43.75% (n = 21), both lower than in Group I.

Discussion

The study found that patients with varying durations of untreated psychosis and admitted under different types of hospitalization formed a heterogeneous group. In Group I, common features included pseudohallucinatory experiences, the syndrome of mental automatism with delusional ideas of various content (persecution, influence), their subsequent “paraphrenization” with the inclusion of “mild catatonia” symptoms, and psychomotor agitation with chaotic, aggressive, or autoaggressive behavior. These factors led to involuntary hospitalization among individuals who had gone without pharmacological treatment for an extended period. Disorganized thinking, frequently observed in this group, further impaired self-regulation and decision-making [24], exacerbating the current mental state and hindering the ability to understand and follow professional recommendations [25]. At the initial stage, such disorganization prevents patients from articulating a coherent rationale for treatment, necessitating more decisive interventions such as involuntary hospitalization [26][27].

A lack of insight into one’s condition and the need for treatment in involuntarily hospitalized individuals undermines adherence and complicates effective psychopharmacotherapy. In contrast, patients admitted voluntarily are better adapted in professional, social, and personal spheres, and more critical in assessing both the necessity of treatment and the effectiveness of medications [28][29].

Severe psychotic symptoms, high levels of psychopathization, and personality traits of a dysthymic, anxious, or excitable nature were predictors of prolonged untreated psychosis and a high likelihood of involuntary hospitalization. Unmotivated, impulsive, or autoaggressive behavior; pseudohallucinatory experiences of an imperative or threatening nature; delusional ideas of persecution or influence; and disorganized thinking all diminish the ability to make independent decisions and seek help. This results in significant delays in therapy and the eventual need for inpatient treatment without the patient’s consent. Conversely, a lower degree of psychopathization, anxious-dysthymic or pedantic traits, and moderately expressed psychotic symptoms were associated with timely psychiatric consultation and favorable treatment outcomes [30].

A reverse relationship is also possible: a key barrier to initiating treatment is denial of mental health problems, coupled with fear of social judgment, job loss, or strain in family relationships, limited awareness of symptoms and of treatment options, and previous negative experiences with healthcare services. These factors prolong the delay in seeking help and increase the risk of involuntary hospitalization [31].

The issue of procedural incapacity (linked to psychotic symptoms that substantially impair comprehension and decision-making) requires a comprehensive approach, taking into account legal, ethical, and medical aspects. Across different countries, policies on this matter are shaped by national legislation, cultural traditions, and the development of healthcare systems. Due to a lack of critical insight, most patients admitted in an acute state undergo involuntary hospitalization with mandatory judicial review. While criteria vary internationally, most legal systems rely on the following principles: danger to self, danger to others, the necessity of treatment that cannot be provided outside a hospital, and lack of awareness of illness severity resulting in refusal of voluntary treatment [32].

In summary, both prolonged untreated psychosis (increasing the likelihood of involuntary psychiatric hospitalization) and a long-standing illness accompanied by a lack of critical self-assessment, fear of stigma, and reluctance to seek help present major obstacles to timely intervention.

Conclusion

A prolonged duration of untreated psychosis (DUP) significantly exacerbates the severity of psychotic symptoms and increases the likelihood of involuntary psychiatric hospitalization. In contrast, a short DUP is associated with a more favorable prognosis and a reduced need for involuntary hospitalization. Timely diagnosis and early treatment initiation are key factors in improving clinical outcomes and lowering the risk of involuntary hospitalization.

Analysis of two patient groups confirmed that DUP is a critical predictor for involuntary hospitalization. Extended delays in therapeutic intervention during a psychotic episode negatively affect social functioning. Patients in Group I showed marked social maladaptation, including deterioration in professional and personal relationships. Those whose first psychotic episode remained untreated for more than three months were significantly more likely to require involuntary hospitalization than patients admitted within the first month after symptom onset.

Factors contributing to delayed psychiatric consultation include poor insight into one’s condition, lack of awareness of symptom severity, and postponement of seeking professional help. These lead to prolonged treatment delays, worsening the clinical course, and increasing the probability of compulsory admission.

Reducing DUP requires a comprehensive, multidisciplinary approach involving psychiatrists, psychologists, and social workers. Preventive strategies such as public education campaigns to improve recognition of early signs of mental illness and to emphasize the importance of prompt medical attention can improve recovery prospects and substantially lower the risk of involuntary hospitalization.

References

1. Kraguljac NV, Anthony T, Morgan CJ, Jindal RD, Burger MS, Lahti AC. White matter integrity, duration of untreated psychosis, and antipsychotic treatment response in medication-naïve first-episode psychosis patients. Mol Psychiatry. 2021;26(9):5347-5356. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-020-0765-x

2. Murru A, Carpiniello B. Duration of untreated illness as a key to early intervention in schizophrenia: A review. Neurosci Lett. 2018;669:59-67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neulet.2016.10.003

3. Pelizza L, Leuci E, Quattrone E, Azzali S, Pupo S, et al. Short-term disengagement from early intervention service for first-episode psychosis: findings from the "Parma Early Psychosis" program. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2024;59(7):1201-1213. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-023-02564-3

4. Dolz M, Tor J, Puig O, de la Serna E, Muñoz-Samons D, et al. Clinical and neurodevelopmental predictors of psychotic disorders in children and adolescents at clinical high risk for psychosis: the CAPRIS study. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2024;33(11):3925-3935. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-024-02436-4

5. Baeza I, de la Serna E, Mezquida G, Cuesta MJ, Vieta E, et al. Prodromal symptoms and the duration of untreated psychosis in first episode of psychosis patients: what differences are there between early vs. adult onset and between schizophrenia vs. bipolar disorder? Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2024;33(3):799-810. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-023-02196-7

6. Schnack HG, van Haren NE, Nieuwenhuis M, Hulshoff Pol HE, Cahn W, Kahn RS. Accelerated Brain Aging in Schizophrenia: A Longitudinal Pattern Recognition Study. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173(6):607-616. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2015.15070922

7. Stone WS, Cai B, Liu X, Grivel MM, Yu G, et al. Association Between the Duration of Untreated Psychosis and Selective Cognitive Performance in Community-Dwelling Individuals With Chronic Untreated Schizophrenia in Rural China. JAMA Psychiatry. 2020;77(11):1116-1126. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.1619

8. Sullivan SA, Carroll R, Peters TJ, Amos T, Jones PB, et al. Duration of untreated psychosis and clinical outcomes of first episode psychosis: An observational and an instrumental variables analysis. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2019;13(4):841-847. https://doi.org/10.1111/eip.12676

9. Aikawa S, Kobayashi H, Nemoto T, Matsuo S, Wada Y, et al. Social anxiety and risk factors in patients with schizophrenia: Relationship with duration of untreated psychosis. Psychiatry Res. 2018;263:94-100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2018.02.038

10. Fond G, Boyer L, Andrianarisoa M, Godin O, Brunel L, et al. Risk factors for increased duration of untreated psychosis. Results from the FACE-SZ dataset. Schizophr Res. 2018;195:529-533. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2017.08.058

11. Goff DC, Zeng B, Ardekani BA, Diminich ED, Tang Y, et al. Association of Hippocampal Atrophy With Duration of Untreated Psychosis and Molecular Biomarkers During Initial Antipsychotic Treatment of First-Episode Psychosis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018;75(4):370-378. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.4595

12. Guo X, Li J, Wei Q, Fan X, Kennedy DN, et al. Duration of untreated psychosis is associated with temporal and occipitotemporal gray matter volume decrease in treatment naïve schizophrenia. PLoS One. 2013;8(12):e83679. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0083679

13. Ajnakina O, Stubbs B, Francis E, Gaughran F, David AS, et al. Hospitalisation and length of hospital stay following first-episode psychosis: systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Psychol Med. 2020;50(6):991-1001. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291719000904

14. Laureano CD, Laranjeira C, Querido A, Dixe MA, Rego F. Ethical Issues in Clinical Decision-Making about Involuntary Psychiatric Treatment: A Scoping Review. Healthcare (Basel). 2024;12(4):445. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12040445

15. Rodrigues R, MacDougall AG, Zou G, Lebenbaum M, Kurdyak P, et al. Involuntary hospitalization among young people with early psychosis: A population-based study using health administrative data. Schizophr Res. 2019;208:276-284. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2019.01.043

16. Walker S, Mackay E, Barnett P, Sheridan Rains L, Leverton M, et al. Clinical and social factors associated with increased risk for involuntary psychiatric hospitalisation: a systematic review, meta-analysis, and narrative synthesis. Lancet Psychiatry. 2019;6(12):1039-1053. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30406-7

17. Wang DWL, Colucci E. Should compulsory admission to hospital be part of suicide prevention strategies? BJPsych Bull. 2017;41(3):169-171. https://doi.org/10.1192/pb.bp.116.055699

18. Akther SF, Molyneaux E, Stuart R, Johnson S, Simpson A, Oram S. Patients' experiences of assessment and detention under mental health legislation: systematic review and qualitative meta-synthesis. BJPsych Open. 2019;5(3):e37. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2019.19

19. Otis M, Barber S, Amet M, Nicholls D. Models of integrated care for young people experiencing medical emergencies related to mental illness: a realist systematic review. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2023;32(12):2439-2452. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-022-02085-5

20. Chinarev V.A., Malinina E.V. The First Psychotic Episode: Clinical, Diagnostic Aspects, and Therapeutic Approaches. Doctor.Ru. 2024;23(7):102-112. (In Russ.) https://doi.org/10.31550/1727-2378-2024-23-7-102-112

21. Di Lorenzo R, Reami M, Dragone D, Morgante M, Panini G, et al. Involuntary Hospitalizations in an Italian Acute Psychiatric Ward: A 6-Year Retrospective Analysis. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2023;17:3403-3420. https://doi.org/10.2147/PPA.S437116

22. Langeveld JH, Hatløy K, Ten Velden Hegelstad W, Johannessen JO, Joa I. The TIPS family psychoeducational group work approach in first episode psychosis and related disorders: 25 years of experiences. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2025;19(1):e13591. https://doi.org/10.1111/eip.13591

23. Chinarev V.A. Clinical, functional and personal recovery as a guideline in the rehabilitation of patients who have suffered a first psychotic episode. International Research Journal. 2024;9(147). (In Russ.) https://doi.org/10.60797/IRJ.2024.147.86

24. Ma, HJ., Zheng, YC., Shao, Y, Xie B. Status and clinical influencing factors of involuntary admission in chinese patients with schizophrenia. BMC psychiatry. 2022;22(1):818. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-022-04480-3

25. Silva M, Antunes A, Azeredo-Lopes S, Loureiro A, Saraceno B, et al. Factors associated with involuntary psychiatric hospitalization in Portugal. Int J Ment Health Syst. 2021;15(1):37. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13033-021-00460-4

26. Müller M, Brackmann N, Homan P, Vetter S, Seifritz E, et al. Predictors for early and long-term readmission in involuntarily admitted patients. Compr Psychiatry. 2024;128:152439. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2023.152439

27. Lin CH, Chan HY, Wang FC, Hsu CC. Time to rehospitalization in involuntarily hospitalized individuals suffering from schizophrenia discharged on long-acting injectable antipsychotics or oral antipsychotics. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol. 2022;12:20451253221079165. https://doi.org/10.1177/20451253221079165

28. Rzhevskaya NK, Ruzhenkova VV, Retyunskiy KYu., Shvets K.N., Khamskaya I.S. Clinical and psychopatological features and psychopharmacotherapy of patients with the first episode of schizophrenia hospitalized in a psychiatric hospital with and without voluntary consent. Research Results in Biomedicine. 2023;9(2):278-288. (In Russ.) https://doi.org/10.18413/2658-6533-2023-9-2-0-10

29. Kravchenko N.E., Zikeev S.A. Acute psychotic conditions as a basis emergency hospitalization of miscellaneous adolescents paul by psychiatric emergency care teams. Sovremennaya terapiya v psikhiatrii i nevrologii. 2024;1:19-22. (In Russ.) eLIBRARY ID: 63361849 EDN: EWTGOY

30. Kravchenko N.E., Zikeev S.A. Foundations for emergency hospitalization of adolescents with psychotic disorders. Sovremennaya terapiya v psikhiatrii i nevrologii. 2021;3-4:21- 24. (In Russ.) eLIBRARY ID: 47716122 EDN: XGPPRR

31. Maina G, Rosso G, Carezana C, Mehanović E, Risso F, et al. Factors associated with involuntary admissions: a registerbased cross-sectional multicenter study. Ann Gen Psychiatry. 2021;20(1):3. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12991-020-00323-1

32. Saya A, Brugnoli C, Piazzi G, Liberato D, Di Ciaccia G, et al. Criteria, Procedures, and Future Prospects of Involuntary Treatment in Psychiatry Around the World: A Narrative Review. Front Psychiatry. 2019;10:271. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00271

About the Authors

V. A. ChinarevRussian Federation

Vitaly Al.Chinarev, psychiatrist, head of the ninth men's Clinical Psychiatric Department of the primary episode; assistant at the Department of Psychiatry

Chelyabinsk

Competing Interests:

Authors declare no conflict of interest

E. V. Malinina

Russian Federation

Elena V. Malinina, Dr. Sci. (Med.), Professor, head of the Department of Psychiatry

Chelyabinsk

Competing Interests:

Authors declare no conflict of interest

Review

For citations:

Chinarev V.A., Malinina E.V. The impact of the duration of untreated psychosis on the risk of involuntary hospitalization during the first psychotic episode. Medical Herald of the South of Russia. 2025;16(2):65-74. (In Russ.) https://doi.org/10.21886/2219-8075-2025-16-2-65-74