Scroll to:

Targeted therapy of bronchial asthma in children

https://doi.org/10.21886/2219-8075-2022-13-2-134-140

Abstract

Objective: to evaluate the clinical efficacy of targeted therapy with omalizumab in children with moderate to severe uncontrolled bronchial asthma.

Materials and methods: 7 children receiving omalizumab therapy in a hospital and polyclinic of the Ufa City Children’s Clinical Hospital No. 17 were under observation. In accordance with the instructions for use, the monoclonal antibody drug omalizumab was administered subcutaneously every 2-4 weeks. The dosage of the drug was determined based on the child’s body weight and the initial level of serum IgE. The anamnesis of life and disease, the results of instrumental and laboratory research methods, the results of AST and c-AST tests were studied in all the children studied.

Results: against the background of therapy with omalizumab in children, there was a significant decrease in the frequency of daytime symptoms (p=0.0179), a decrease in the frequency of night symptoms (p=0.0233), increased physical activity (p=0.0179), a decrease in the need for bronchodilators (p=0.0179), an increase in FEV1 according to spirography (p=0.0431), a decrease in the volume of basic anti-inflammatory therapy with a decrease in the dose of IGCS in 71.43% of patients (p=0.0425), a significant increase in the number of AST and c–AST test scores: before treatment 12 [10; 13] points, against the background of treatment - 23 [20; 25] points, (p=0.0277). During the follow-up period of therapy with omalizumab, no serious adverse reactions were detected.

Conclusion: thus, targeted therapy using omalizumab is clinically effective in children with moderate to severe uncontrolled bronchial asthma.

For citations:

Fayzullina R.M., Sannikova A.V., Shangareeva Z.A., Absalyamova N.T., Valeeva Zh.A. Targeted therapy of bronchial asthma in children. Medical Herald of the South of Russia. 2022;13(2):134-140. (In Russ.) https://doi.org/10.21886/2219-8075-2022-13-2-134-140

Introduction

Currently, more than 300 million people worldwide have bronchial asthma (BA)1. BA prevalence among the adult population of Russia is 6.9%, among children, it reaches 10–12% [1], while 5–10% of patients have a severe disease [2]. Patients with severe and moderate BA, which is not controlled by appropriate treatment, requires high doses of inhaled and systemic glucocorticosteroids, and is accompanied by the development of severe flares, pose a special challenge [3]. The currently proven molecular and clinical heterogeneity of BA determines the personalized approach to each individual patient. One of the effective methods of pathogenetic BA therapy is the use of monoclonal antibody preparations designed for patients with the T2-mediated type of inflammation.

Omalizumab is a recombinant humanized monoclonal antibody that binds free immunoglobulin E (IgE) and prevents its interaction with receptors on mast cells, basophils, and other T2 inflammatory participants. Currently, omalizumab is approved in the Russian Federation for therapy of uncontrolled moderate to severe atopic BA in children over 6 years old, chronic spontaneous urticaria, seasonal and year-round allergic rhinitis in patients over 12 years old, polyposis rhinosinusitis in patients over 18 years old. Treatment with omalizumab in patients with BA leads to a decrease in the disease symptoms, an increase in the external respiratory function, a decrease in the need for bronchodilators, an improvement in the quality of life, and a decrease in the risk of flares and hospitalizations [4][5].

To date, there are few studies on the use of genetically engineered biological omalizumab in children in the Russian Federation, which presents a need for further research on this topic.

The article presents the results of the authors’ own observation of children with moderate to severe uncontrolled BA receiving omalizumab.

The study objective was to evaluate the clinical efficacy of targeted therapy with omalizumab in children with moderate to severe uncontrolled BA.

Materials and methods

An observational study without a comparison group was conducted. The observation was carried out from March 2019 to March 2022. The study objects were 7 children with moderate and severe uncontrolled BA receiving basic anti-inflammatory therapy with omalizumab at the inpatient and outpatient clinics of Ufa City Children's Clinical Hospital No. 17. BA was diagnosed in accordance with the "Bronchial asthma" clinical guidelines (Moscow, 2021) [6]. The BA severity and control level were determined in accordance with generally accepted classifications [6][7].

The inclusion criteria in the study were the following: 1) age of children from 6 to 18 years; 2) body weight more than 20 kg; 3) moderate and severe uncontrolled asthma; 4) proven atopic etiology of the disease; 5) increased baseline serum IgE; 6) no contraindications to anti-IgE therapy. The exclusion criteria from the study were as follows: 1) age under 6 and over 18 years; 2) body weight less than 20 kg; 3) mild and moderate BA, well controlled by stages 1–4 of therapy; 4) unproven atopic etiology of the disease; 5) normal or very high baseline serum IgE, more than 1,500 IU/ml; 6) contraindications to anti-IgE therapy.

In the present study, all patients received omalizumab, a genetically engineered biological drug. In accordance with the instructions for use, the dose and mode of drug administration were determined at the first contact/hospitalization of patients; the drug dose was calculated based on the child's body weight and baseline serum IgE. Omalizumab was administered subcutaneously once every 2 or 4 weeks.

Life history and disease history (hereditary predisposition, BA duration and severity, the frequency and severity of flares, the amount of baseline anti-inflammatory therapy, concomitant allergic pathology), results of instrumental (spirography) and laboratory methods of investigation (serum IgE, clinical blood count with eosinophil number), specific allergic diagnostics (allergen-specific immunoglobulins E, skin allergic tests) were studied in all the examined children. The Asthma Control Test (ACT) questionnaire for adolescents over 12 years of age and adults and the Children Asthma Control Test (c-ACT) for children aged 4 to 11 years (before and against the backdrop of omalizumab therapy) were offered to assess the control of BA.

Statistical processing of the obtained research results was carried out using the Statistica 10.0 applications package. Methods for small samples (Mann-Whitney U test and Fisher exact test) were used for statistical analysis. Wilcoxon's t-test was used to compare two independent variables. The Spearman rank correlation criterion was used to determine the relationship of individual quantitative characteristics. Continuous variables were presented as the median and interquartile range (25% and 75% quartiles): Me [Q1; Q3]. The results were considered statistically significant at p <0.05.

Results

There were 5 girls (71.43%), 2 boys (28.57%), and the mean age was 12.86 [ 9; 17] years among the examined children.

Three (42.86%) and four (57.14%) children were diagnosed with moderate and severe persistent BA, respectively. Lack of disease control was observed in all patients studied, and 3–4 steps of baseline anti-inflammatory therapy (medium/high doses of inhaled glucocorticosteroids (iGCs) in combination with long-acting β2-agonists (LABA) and/or leukotriene receptor antagonists (LRA)) were used for treatment. BA control was assessed with high compliance and the proper inhalation technique.

The average duration of BA in the examined children was 10 [ 3; 14] years. At the same time, the atopic nature of the disease was proved in the laboratory. Polyvalent sensitization (based on allergen specific IgE and skin allergological tests) was detected in 100% of the subjects: household and pollen – in 85.71%, epidermal – in 71.43%, food – in 28.57% of children. The fungal sensitization has not been established. A burdened allergic history occurred in 6 of the examined children (85.71%): on the mother's side 42.86%, on the father's side 28.57%, and on the second-line relatives' side 14.29%. In 85.71% of children, unsatisfactory living conditions which were due to upholstered furniture (85.71%), books on open shelves (85.71%), flowers (85.71%), carpets and palases (28.57%), feather pillows (28.57%), cockroaches (28.57%), pets (27.14%), dampness and mold (14.29%) in a residential area were found.

Respiratory infections (100%), contact with an allergen (100%), physical activity (85.71%), and changes in weather conditions (85.71%) were noted as trigger factors of asthma flares in children.

Analysis of concomitant allergic pathology showed that allergic rhinitis and atopic dermatitis accompanied BA in 100%, allergic urticaria in 28.57%, and allergic conjunctivitis in 14.29% of children.

All the examined children had increased total serum IgE which is a prerequisite for therapy with omalizumab, recombinant humanized monoclonal antibodies against IgE. The average serum IgE in children was 397.0 [ 225; 665.5] IU/ml. The average dose of omalizumab in children was 300 [ 300; 450] mg (Table 1).

Table 1

The dose of omalizumab in the studied children, based on body weight and baseline serum IgE level, mg

|

Baseline serum IgE level (ME/ml) |

Body weight (kg) |

||||||

|

23 |

28 |

34 |

46 |

46 |

56 |

57 |

|

|

475 |

300 mg |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

225 |

|

150 mg |

|

|

|

|

|

|

847 |

|

|

600 mg |

|

|

|

|

|

200 |

|

|

|

300 mg |

|

|

|

|

397 |

|

|

|

|

450 mg |

|

|

|

300 |

|

|

|

|

|

300 mg |

|

|

655.5 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

300 mg |

The duration of omalizumab therapy in children with BA was on average 13 [ 10; 35] months.

BA control in the examined children showed that against the backdrop of omalizumab therapy, there was a significant decrease in the frequency of daytime symptoms (Z=2.3664; p=0.0179), a decrease in the frequency of nocturnal symptoms (Z=2.2678; p=0.0233), increased physical activity (Z=2.3664; p=0.0179), and a reduced need for bronchodilators (Z=2.3664; p=0.0179). The effectiveness of omalizumab therapy was confirmed by a significant increase in forced exhalation volume (FEV1) in children, according to spirography: before therapy, FEV1 was 86 [ 78; 92]%, and against the backdrop of therapy, it was 88 [ 86; 95]% (Z=2.0226; p=0.0431). It is important to note that against the backdrop of omalizumab therapy, it was possible to reduce the baseline anti-inflammatory therapy with a decrease in the dose of iGCs in 71.43% of patients (5 children), Z=2.0284, p=0.0425.

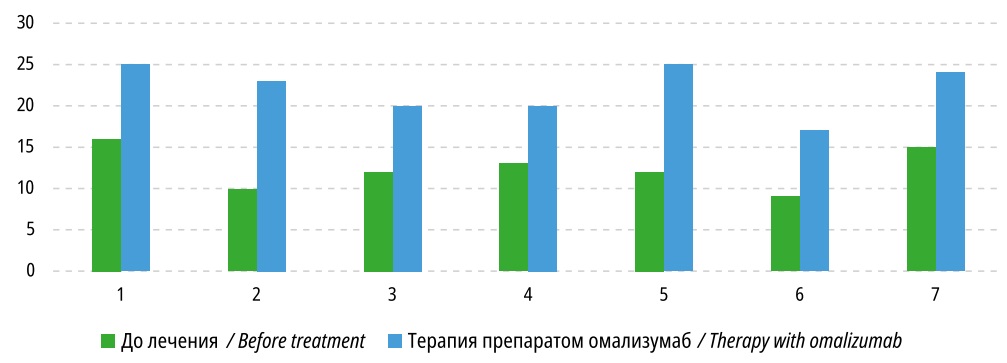

The improvement of disease control against the backdrop of omalizumab therapy was evidenced by a significant increase in the ACT and c-ACT test scores in all examined children: before the start of treatment, the average test scores were 12 [ 10; 13] points, and against the backdrop of treatment were 23 [ 20; 25] scores (p=0.0277) (Figure 1).

According to the c-ACT test offered to children aged 6 to 11 years (n=3), against the backdrop of omalizumab therapy, the scores in all patients ranged from 20 to 23 (control availability). The ACT test in children over 12 years of age (n=4) showed that against the backdrop of omalizumab therapy, one child had complete control, two had partial control, and one child's asthma could not be sufficiently controlled.

Figure 1. Results of ACT, c-ACT test in children with omalizumab therapy, scores (p<0.05)

During omalizumab therapy, the clinical course of concomitant allergic pathology also improved: the complete absence of symptoms of allergic rhinitis (remission) was observed in 85.71% of children, atopic dermatitis – in 42.86%.

It is important to note that the study of the dependence of the omalizumab therapy (months) duration did not reveal statistically significant relationships with the result of ACT and c-ACT tests (m= -0.1272; p>0.05), the flare frequency (m= -0.1443; p>0.05), daytime symptoms (m= 0.1443; p>0.05), nocturnal symptoms (m= 0.4743; p>0.05), and the need for bronchodilators (m= 0.0398) in the course of treatment.

Analysis of the results of clinical blood and urine tests and blood chemistry during treatment revealed no deviations from age norms. The exception was the increased peripheral blood eosinophils in all patients examined, the average level of blood eosinophils was 7 [ 6; 10]%.

No serious adverse reactions were detected during the observation period of omalizumab therapy. One child (14.29%) had local reactions as hyperemia in the injection area, which did not require the drug withdrawal.

Discussion

BA is one of the most common chronic heterogeneous diseases of the respiratory tract. The main objective of BA therapy is to achieve disease control. Most BA patients respond well to conventional anti-inflammatory therapy; however, in the overall disease structure, 5 to 10% of patients remain refractory to standard baseline anti-inflammatory therapy [8]. The modern management of BA patients requires an in-depth analysis of risk factors, taking into account the clinical and biological phenotypes and endotypes of the disease.

More than 80% of all cases in children account for allergic IgE-mediated BA [9]. Key mediators of inflammation in atopic BA are immunoglobulins E, and hereditary predisposition to IgE hyperproduction is an important condition for atopic disease [10]. The results of the present research showed a high incidence of a burdened family allergic history in children with atopic BA (85.71%).

According to numerous studies, BA in children is accompanied by poor disease control due to a number of factors. For example, the results of the ENFUMOSA [4] and TENOR [5] clinical trials show that sensitization to aeroallergens in 50–90% of patients prevents the achievement of BA control. In the present research, sensitization to aeroallergens (household and pollen) was established in 85.71% of children, and to epidermal ones in 71.43%. Unsatisfactory living conditions were found in 85.71% of the children (upholstered furniture, carpets and carpeting, books on open shelves, flowers, and pets in the dwelling). A number of studies have also shown that comorbid atopic diseases may be the cause of the lack of BA control [6][7]. Similar data were obtained in the authors’ observation, where a high frequency of comorbid allergic pathology (allergic rhinitis, atopic dermatitis, allergic urticaria, allergic conjunctivitis) was found in all children examined (100%). One of the most common factors contributing to BA flares in children is viral respiratory infections, which in combination with atopy is an adverse factor in achieving control [11]. According to the authors’ data, respiratory infections served as a flare trigger factor for the disease in all examined children with uncontrolled BA (100%).

Thus, in the present research, the presence of a hereditary predisposition to IgE hyperproduction, proven sensitization to allergens, elevated serum IgE, and uncontrolled disease were indications for the prescription of humanized monoclonal antibodies against IgE-omalizumab in children with moderate to severe BA. According to the elevated baseline serum IgE (397.0 [ 225; 665.5] IU/ml), the dose of omalizumab in children was 300 [ 300; 450] mg, and the duration of therapy was 13 [ 10; 35] months.

The research results showed that omalizumab was clinically effective in moderate to severe uncontrolled BA in children and was accompanied by a significant reduction in the frequency of daytime and nocturnal symptoms, increased physical activity, decreased need for bronchodilators, i.e. achievement of disease control. Evidence for the omalizumab effectiveness in the treatment of patients with allergic BA has been demonstrated in clinical trials and systematic reviews, the results of which also show that the omalizumab administration in patients with severe BA is accompanied by a significant reduction in the flare frequency, increased number of patients with the possibility to reduce or cancel the iGCs, reduced need for bronchodilators, and in general improved BA control [12][13].

The study results of the Russian researchers demonstrate the efficacy and safety of long-term therapy with omalizumab (more than 4 years) in 47 children with severe persistent uncontrolled BA [14], which show that against the backdrop of omalizumab therapy, the frequency of significant severe flares in 6 months from the start of treatment decreases, the number of daily symptoms and the need for emergency drugs (15.78 times/month) decrease. The same study showed positive dynamics of pulmonary function parameters and reduction of baseline iGCs therapy after four years of therapy. In this research, the effectiveness of omalizumab therapy was confirmed by a significant increase in FEV1 from 86 [ 78; 92]% to 88 [ 86; 95]% on treatment. According to the results of the authors’ observation, against the backdrop of omalizumab therapy, the baseline anti-inflammatory therapy with iGCs decreased in 71.43% of children.

An important indicator in assessing BA control is the subjective assessment of patients. According to the authors’ data, before starting omalizumab therapy, the average ACT and c-ACT test score was 12 scores (14 [ 10; 13]), which corresponded to uncontrolled BA. According to the c-ACT test, against the backdrop of omalizumab therapy, the score ranged from 20 to 23 (control availability). The ACT test showed that against the backdrop of omalizumab therapy, 25% of children had complete control, 50% had partial control, and in 25% (1 patient with severe BA), asthma could not be sufficiently controlled. In the authors’ opinion, on the one hand, the cause of this patient's lack of BA control was the irregular use of basal anti-inflammatory drugs. On the other hand, in refractory BA, along with an inflammatory response, structural changes (bronchial remodeling) with irreversible airway obstruction develop in the airways [15]. Important in this case is the duration of the disease which in children in this research averaged 10 years.

At the same time, this study revealed no significant correlations between the BA duration and the frequency of flares, the need for bronchodilators, and the results of ACT and c-ACT tests, which indicates the effectiveness of omalizumab treatment from the first months of therapy.

Thus, the efficacy and safety of omalizumab are confirmed both in real clinical practice in multicenter studies [16] and in randomized clinical observations [17][18].

Conclusion

Targeted omalizumab therapy is clinically effective in patients with BA resistant to traditional therapy. The authors’ observations show a significant reduction in the frequency of daytime symptoms, nocturnal symptoms, reduced need for emergency drugs, increased physical activity, increased volume of FEV1 according to spirography, reduced baseline anti-inflammatory therapy, and achieving control of BA by ACT and c-ACT tests against the backdrop of omalizumab use in the treatment of moderate and severe uncontrolled BA in children.

1. Global Initiative for Asthma. Global Strategy for Asthma Management and Prevention. 2018. Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA). Available from: http://www.ginasthma.org

References

1. Nacionalnaja programma: Bronhialnaja astma u detej. Strategija lechenija i profilaktika. Moscow: Original-maket; 2017.

2. Kolbin A.S., Namazova-Baranova L.S., Vishnjova E.A., Frolov M.Ju., Galankin T.L. et al. Pharmaco-Economic Analyzis of Treating Severe Uncontrolled Child Asthma with Omalizumab — Actual Russian Clinical Practice Data. Pediatricheskaya farmakologiya — Pediatric pharmacology. 2016;13 (4): 345–353. (In Russ.) 2016; 13 (4): 345–353. DOI: 10.15690/ pf.v13i4.1606

3. Nenasheva N.M., Averyanov A.V., Ilina N.I., Avdeev S.N., Osipova G.L. et al. Comparative Study of Biosimilar Genolar® Clinical Efficacy оп the Randomized Phase III Study Results. Pulmonologiya = Russian Pulmonology. 2020;30(6):782–796. (In Russ.) DOI: 10.18093/0869-0189-2020-30-6-782-796.

4. Molimard M, Mala L, Bourdeix I, Le Gros V. Observational study in severe asthmatic patients after discontinuation of omalizumab for good asthma control. Respir Med. 2014;108(4):571–576. DOI: 10.1016/j. rmed.2014.02.003.

5. Kozlov V.A., Savchenko A.A., Kudryavtsev I.V., Kozlov I.G., Kudlay D.A., Prodeus A.P., Borisov A.G. Clinical immunology. Krasnoyarsk: Polikor; 2020. 386 p. (In Russ.) DOI: 10.17513/np.438

6. Klinicheskie rekomendacii. Bronhialnaja astma. – Moscow, 2021.

7. Klinicheskie rekomendacii. Bronhialnaja astma u detej. – Moscow, 2019.

8. Bousquet J, Mantzouranis E, Cruz A.A. et al. Uniform definition of asthma severity, control, and exacerbations: document presented for the World Health Organization Consultation on Severe Asthma. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2010; 126 (5): 926–938. DOI: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.07.019.

9. Wenzel S. Severe asthma: from characteristics to phenotypes to endotypes. Clin. Exp. Allergy. 2012; 42 (5): 650–658. DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2011.03929.x.

10. Kniajeskaia N.P., Anaev E.H., Belevskiy A.S., Kameleva A.A., Safoshkina E.V., Kirichenko N.D. Omalizumab and modification of bronchial asthma natural course. Meditsinskiy sovet = Medical Council. 2021;(16):17-25. (In Russ.) DOI: 10.21518/2079-701X-2021-16-17-25

11. Heymann PW, Platts-Mills TAE, Woodfolk JA, Borish L, Murphy DD, Carper HT. et al. Understanding the asthmatic response to an experimental rhinovirus infection: Exploring the effects of blocking IgE. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020;146(3):545–554. DOI: 10.1016/j.jaci.2020.01.035

12. Rodrigo GJ, Neffen H, Castro-Rodriguez JA. Efficacy and safety of subcutaneous omalizumab vs placebo as addon therapy to corticosteroids for children and adults with asthma: a systematic review. Chest. 2011; 139 (1): 28–35. DOI: 10.1378/chest.10-1194.

13. Hanania NA, Alpan O, Hamilos DL et al. Omalizumab in severe allergic asthma inadequately controlled with standard therapy: a randomized trial. Ann. Intern. Med. 2011; 154 (9): 573–582. DOI: 10.7326/0003-4819-154-9-20110 5030-00002.

14. Elena A. Vishneva, Leyla S. Namazova-Baranova, Elena A. Dobrynina, Anna A. Alekseeva, Vladimir I. Smirnov, Julia G. Levina, Vera G. Kalugina, Kamilla E. Efendieva, Konstantin S. Volkov. The Long-Term Omalizumab Therapy in Children with Severe Persistent Uncontrolled Asthma: Evaluation of the Outcomes According to the Data of the Hospital Patient Registry. Pediatricheskaya farmakologiya — Pediatric pharmacology. 2018; 15 (2): 149–158. (In Russ.) DOI: 10.15690/pf.v15i2.1877

15. Avdeev S.N., Nenasheva N.M., Zhudenkov K.V., Petrakovskaya V.A., Izyumova G.V. Prevalence, morbidity, phenotypes and other characteristics of severe bronchial asthma in Russian Federation. Russian Pulmonology. 2018; 28 (3): 341–358 (In Russ.). DOI: 10.18093/0869- 0189-2018-28-3-341-358

16. Niven RM, Saralaya D, Chaudhuri R. Impact of omalizumab on treatment of severe allergic asthma in UK clinical practice: a UK multicentre observational study (the APEX II study). BMJ Open. 2016;6(8):e011857. DOI: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011857.

17. Kupryś-Lipińska I, Majak P, Molinska J, Kuna P. Effectiveness of the Polish program for the treatment of severe allergic asthma with omalizumab: a single-center experience. BMC Pulm Med. 2016;16(1):61. DOI: 10.1186/s12890-016-0224-2.

18. Ledford D, Busse W, Trzaskoma B. A randomized multicenter study evaluating Xolair persistence of response after longterm therapy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;140(1):162–169.e2. DOI: 10.1016/j.jaci.2016.08.054.

About the Authors

R. M. FayzullinaRussian Federation

Reseda M. Faizullina, Dr. Sci. (Med.), Professor of the Department of Faculty Pediatrics with Courses of Pediatrics, Neonatology and the IDPO Simulation Center

Ufa

A. V. Sannikova

Russian Federation

Anna V. Sannikova, Cand. Sci. (Med.), associate Professor of the Department of Faculty Pediatrics with Courses of Pediatrics, Neonatology and the IDPO Simulation Center

Ufa

Z. A. Shangareeva

Russian Federation

Ziliya A. Shangareeva, Cand. Sci. (Med.), associate Professor of the Department of Faculty Pediatrics with Courses of Pediatrics, Neonatology and the IDPO Simulation Center

Ufa

N. T. Absalyamova

Russian Federation

Nursilya T. Absalyamova, Chief Physician

Ufa

Zh. A. Valeeva

Russian Federation

Zhanna A. Valeeva, Cand. Sci. (Med.), associate Professor, Deputy Chief Physician for the polyclinic

Ufa

Review

For citations:

Fayzullina R.M., Sannikova A.V., Shangareeva Z.A., Absalyamova N.T., Valeeva Zh.A. Targeted therapy of bronchial asthma in children. Medical Herald of the South of Russia. 2022;13(2):134-140. (In Russ.) https://doi.org/10.21886/2219-8075-2022-13-2-134-140